For the last few months I’ve been writing about the challenges facing people at the top of large, hierarchical organizations, with the story of the US military’s failure in Vietnam (as told by David Halberstam) as a running example. You guys are probably getting tired of this particular example, so I’m going to make one more point and then I’ll move on to other subjects.

I’ve argued that the top-down management structures that large organizations adopt severely distort and constrain the information that reaches those at the top, and that this, in turn, causes senior management to make systematically poor decisions. Smart managers of a certain bent grasp this problem and they think they have a solution to it: data! Your subordinates might mislead you, they think, but if you have the raw data you can slice through the layers of obfuscation and get directly to the truth. Managers with an aptitude for math and statistics are especially likely to view number crunching as an alternative (and generally superior) method of understanding the organizations they run.

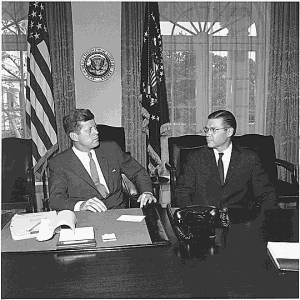

No one better typified this attitude during the Vietnam era than Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara. McNamara was trained in statistics at Harvard Business School, and was a young professor there when the War broke out. He made a name for himself helping to organize the fantastically complex B-29 bomber program, and then went into private industry after the war. He wound up at Ford, where he used his formidable statistical expertise to modernize Ford’s production processes, rising quickly to the position of Ford president.

No one better typified this attitude during the Vietnam era than Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara. McNamara was trained in statistics at Harvard Business School, and was a young professor there when the War broke out. He made a name for himself helping to organize the fantastically complex B-29 bomber program, and then went into private industry after the war. He wound up at Ford, where he used his formidable statistical expertise to modernize Ford’s production processes, rising quickly to the position of Ford president.

When McNamara was tapped to be Secretary of Defense, he brought this same basic attitude to the Pentagon:

There was that confidence which bordered on arrogance, a belief that he could handle it. Perhaps, after all the military weren’t all that good; still they could produce the raw data, and McNamara, who knew data, would go over it carefully and extricate truth from the morass. Thus the portrait of McNamara in those years at his desk, on planes, in Saigon, poring over page after page of data, each platoon, each squad, studying all those statistics. All lies. Talking with reporters and telling them that all the indices were good. He could not have been more wrong; he simply had all the wrong indices, looking for American production indices in an Asian political revolution…

One particular visit seemed to sum it up: McNamara looking for the war to fit his criteria, his definitions. He went to Danang in 1965 to check on the Marine progress there. A marine colonel in I Corps had a sand table showing the terrain and patiently gave the briefing: friendly situation, enemy situation, main problem. McNamara watched it, not really taking it in, his hands folded, frowning a little, finally interrupting. “Now let me see,” McNamara said, “if I have it right, this is your situation,” and then he spouted his own version, all in numbers and statistics. The colonel, who was very bright, read him immediately like a man breaking a code, and without changing stride, went on with the briefing, simply switching his terms, quantifying everything, giving everything in numbers and percentages, percentages up, percentages down, so blatant a performance that it was like a satire. Jack Raymond of the New York Times began to laugh and had to leave the tent. Later that day Raymond went up to McNamara and commented on how tough the situation was up in Danang, but McNamara wasn’t interested in the Vietcong, he only wanted to talk about that colonel, he liked him, that colonel had caught his eye. “That colonel is one of the finest officers I’ve ever met,” he said.

McNamara was more obsessed with statistics than most of his subordinates, but his generals had the same basic attitude:

The American military command thought this was like any other war: you searched out the enemy, fixed him, killed him and went home. The only measure of the war the Americans were interested in was quantitative, and quantitatively, given the immense American fire power, helicopters, fighter-bombers, and artillery pieces, it went very well. That the body count might be a misleading indicator did not penetrate the command; large stacks of dead Vietcong were taken as signs of success. That the French statstics had also been very good right up until 1954, when they gave up, made no impression.

I think McNamara’s number-crunching wizardry actually turned out to be a handicap. When his analysis seemed to be faulty, his instinct was always to examine the data even more closely. But no statistical test is going to tell you that your faulty assumptions have caused you to collect the wrong kind of data. To the contrary, the more deeply engaged you become with a data set, the more oblivious you’re likely to be to the big picture. And so McNamara, like the French before him, pushed forward with the inflated sense of confidence that comes from having precise statistics about the wrong variables.

That bit about “raw numbers” giving people the illusion that they’re in touch with reality is a good point. Part of the problem is that collecting and organising data is its own sort of organisational problem – the numbers aren’t “raw,” they’re as processed as they come. The question is just whether the processing was any good.

Take the death count thing: unless you’re going out and inspecting every corpse yourself, you’re relying on subordinates to count them and classify them as either combatants or civilians. And if you are going out and inspecting corpses, you’ll probably find that there are a lot of cases where making that call is pretty subjective, even before we get to the obvious incentives to misreport. That sort of uncertainty tends to get lost once you’re dealing with “raw data.”

I’m a pastor in the United Methodist Church a very “hierarchical organization” that has been declining. Data collection has been accelerated in the past few years exponentially. Two comments from the below. . .

#1 No matter what you measure it will go up. We learn to measure subjectively particularly when one is rewarded for better numbers.

#2 Not understanding the data seems to create is worse problems than not collecting the data.

Data is just another institutional way to justify existence and punish those who are really doing the job.

A large part of the data problem in Vietnam for the American military, just as it was for the Japanese Navy during WWII, was BS numbers sent up to make yourself look good. At some point, I think we had killed more VCs than there were people in Vietnam.

Once your data process gets corrupted that way, in some sense it doesn’t matter if you’re looking for the right statistics.