If you want to study the deficiencies of large, hierarchical organizations, a good case study is the most powerful hierarchical organization on Earth: the United States military. Our military has long exemplified the dysfunctions of large, hierarchical organization (see, for example, the phrase SNAFU, the American GI’s most eloquent expression of bottom-up thinking). Journalist Thomas Ricks wrote an excellent book about one of our military’s more serious mistakes: the invasion of Iraq. Not surprisngly, PowerPoint played a role in this disaster too:

[Army Lt. General David] McKiernan had another, smaller but nagging issue: He couldn’t get Franks to issue clear orders that stated explicitly what he wanted done, how he wanted to do it, and why. Rather, Franks passed along PowerPoint briefing slides that he had shown to Rumsfeld: “It’s quite frustrating the way this works, but the way we do things nowadays is combatant commanders brief their products in PowerPoint up in Washington to OSD and Secretary of Defense…In lieu of an order, or a frag [fragmentary order], or plan, you get a bunch of PowerPoint slides…[T]hat is frustrating, because nobody wants to plan against PowerPoint slides.”

That reliance on slides rather than formal written orders seemed to some military professionals to capture the essence of Rumsfeld’s amateurish approach to war planning. “Here may be the clearest manifestation of OSD’s contempt for the accumulated wisdom of the military profession and of the assumption among forward thinkers that technology—above all information technology—has rendered obsolete the conventions traditionally governing the preparation and conduct of war,” commented retired Army Col. Andrew Bacevich, a former commander of an armored cavalry regiment. “To imagine that PowerPoint slides can substitute for such means is really the height of recklessness.” It was like telling an automobile mechanic to use a manufacturer’s glossy sales brochure to figure out how to repair an engine.

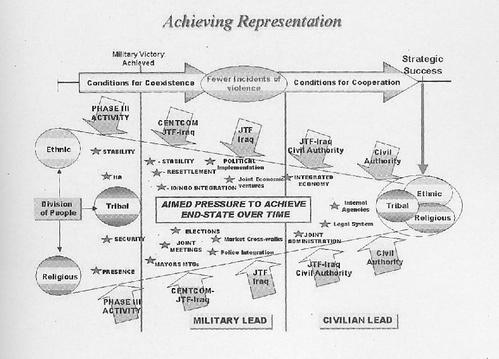

This classic Arms and Influence post points to the PowerPoint slide above, which is reproduced in Ricks’s books from a military presentation on reconstruction planning. It’s a particularly egregious example of PowerPoint thinking. This slide seems to gesture in the general direction of a strategy, but it’s obviously not a coherent plan for reconstruction. One hopes that the slide made more sense to people who heard the accompanying talk, but even then it seems unlikely that it would have had the kind of rigor you’d want for an effective military campaign.

One reaction to a story like this is to just say that Franks and Rumsfeld were bad managers. And they probably were. But Franks and Rumsfeld are hardly the only managers to give their subordinates vague or non-sensical orders.

There’s a parallel between the job of managers and the job of computer programmers. Managers, like programmers, are supposed to control systems (of people rather than silicon) that are far too complicated to understand in their full detail. And they use the same basic strategy that programmers do: abstraction. Just as we give our computers high level instructions (“fetch this website”, “open this file”) and let our software take care of all the messy details, so do managers give their subordinates high-level instructions (“capture this village,” “build these airplanes”) and let their subordinates take care of the details.

And like programmers, managers are often brought low by the problem of leaky abstractions. A strategy that seems plausible when illustrated on a high-level PowerPoint slide might be revealed as tragically inadequate when it comes into contact with reality. Programmers have the crucial advantage that they usually have access to the complete system their abstractions represent. This means that they can take advantage of the tight feedback loops provided by fail-fast design: you run your program, and if it crashes you know you still have work to do. It’s much harder for managers to do this kind of rigorous testing. This is why businesses build prototypes and release products in test markets. It’s why the military spends so much time war-gaming.These strategies are far from perfect. Even the most elaborate wargame is itself a leaky abstraction that will fail to capture all of the nuances of a real war. And managers, unlike programmers, have a serious problem of biased reporting. If a programmer gives a computer instructions that don’t make sense, the computer isn’t shy about pointing that out. In contrast, if a manager gives instructions that don’t make sense (“Find evidence of WMD in Iraq”), the people under him will often bend over backwards to avoid telling their boss unpleasant truths.

Good managers understand the danger of their subordinates telling them telling them what they want to hear. Joel Spolsky has a good story from his days at Microsoft when he had a meeting with Bill Gates. “Bill doesn’t really want to review your spec, he just wants to make sure you’ve got it under control. His standard M.O. is to ask harder and harder questions until you admit that you don’t know, and then he can yell at you for being unprepared.” It’s a little bit cruel, perhaps, but it’s the kind of thing you need to do to successfully manage a large organization.

And of course most managers aren’t as good as Bill Gates. Typical managers are prone to deal in high-level abstractions that have only a tenuous connection to reality. And sometimes the result is like a cartoon character who careens off a cliff but hasn’t yet noticed the 1000-foot drop below him: everything seems fine until the situation gets so bad that your subordinates can no longer sugar-coat it.

And of course most managers aren’t as good as Bill Gates. Typical managers are prone to deal in high-level abstractions that have only a tenuous connection to reality. And sometimes the result is like a cartoon character who careens off a cliff but hasn’t yet noticed the 1000-foot drop below him: everything seems fine until the situation gets so bad that your subordinates can no longer sugar-coat it.

The larger your organization is, the more gut-wrenching the subsequent fall will be. If you’ve only got a couple of layers of management below you, it’s relatively easy to stay in touch with the “facts on the ground” and catch problems early. If you’ve got a dozen layers of bureaucracy below you, like Donald Rumsfeld, it requires a Herculean effort to cut through layer upon layer of half-truths to find out what’s really going on at the bottom of the hierarchy.

I assume you’ve seen the Tufte essay on Powerpoint? http://www.edwardtufte.com/tufte/powerpoint

Interesting. This “leaky abstraction” Powerpoint criticism seems a bit different — or at least more specific — than the problems with PowerPoint information flow identified by Edward Tufte (who you also posted about; how very meta of you). And it seems especially problematic for a project as complex and temporally varying as a war, even if you assume perfect communication between individuals using these slides.

And handing these things down as actual orders? That doesn’t simply fail to protect against abstraction leakage, it effectively induces it.

@epc: yes I linked to Tufte last week.

The current secdef (Gates, ironically) seems to be a bit more reasonable, at least from his desire to cut silly Cold-war era weapons projects.

Not sure about his powerpoint techniques though. 🙂