Jerry Brito points to a BBC interview with Mick Jagger:

People only made money out of records for a very, very small time. When The Rolling Stones started out, we didn’t make any money out of records because record companies wouldn’t pay you! They didn’t pay anyone!

Then, there was a small period from 1970 to 1997, where people did get paid, and they got paid very handsomely and everyone made money. But now that period has gone.

So if you look at the history of recorded music from 1900 to now, there was a 25 year period where artists did very well, but the rest of the time they didn’t.

As Jerry points out, you can go back much further than 1900. When people look back from the year 2100, I think they’ll see the period 1960-2000 as basically a fluke: a brief window of time where technological forces centralized the music industry to an unprecedented degree and drove massive profits to a tiny number of musicians and firms.

As Jerry points out, you can go back much further than 1900. When people look back from the year 2100, I think they’ll see the period 1960-2000 as basically a fluke: a brief window of time where technological forces centralized the music industry to an unprecedented degree and drove massive profits to a tiny number of musicians and firms.

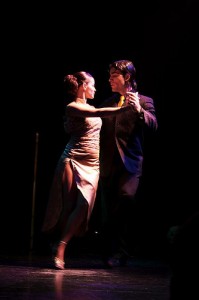

Forty years was long enough to convince everyone that the new structure of the industry was permanent. But it wasn’t. The decentralizing power of the Internet is now returning us to the historical norm, which was for music to be primarily a hobby like tennis or dancing. It is possible to make a living doing these things, but you’re not likely to get rich doing them. And hardly anyone considers that a public policy problem.

The rise and fall of recorded music is no more an aberration than those of the railroad companies or printed news. There’s no “normal” state of affairs, just change over time. So it’s wrong to say “let’s go back to how things should be, the way it was 100 years ago”. First because the market for music today is nothing like it was 100 or 200 years ago: the prominence of music as entertainment is different, the source of funding is different, the technology is different. And second because we don’t have to accept the public policy of 100 years ago, either because the market has changed or because our goals have changed.

While there have certainly always been more music hobbyists than professionals, the overwhelming majority of music we treasure and appreciate today, from Bach and Mozart through the Beatles to Britney and beyond was created strictly for financial gain, by professionals for whom music was their livelihood. I agree that public policy shouldn’t try specifically to make musicians as rich as the Beatles. But the fact that Mozart spent much of his time worrying about his financial problems, and died so tragically young, is not necessarily what we want to define as the “norm” and replicate today.

I think – and this is completely up to personal views and values – that our goal should be to encourage or at least sustain the creation of good, popular, lasting music. Granting that, centuries of history show that this music comes predominantly from professional musicians, so our public policy should arrange for conditions where, at least potentially and in some cases, all the people involved in making music: lyricists, composers, arrangers, vocalists, players, sound engineers, etc. can make a living doing so. Of course technology, crowd taste and even cultural values change through time; the public policy should continually realign with the current goals and circumstances. It should not, in general, be to leave things be and let them sink into their “normal” state, as there isn’t one.

As a side point, tennis is not governed by public policy but rather by free-market forces, and it is interesting to note that the two main tours, ATP and WTA, figured that the way to maintain a high quality level of game is indeed to make sure the best players become rich by playing tennis. “Making people rich” is not an inherently frivolous strategy.

Uri, I don’t think we disagree. My point isn’t that we should go back to the conditions of 1900. My point is that what we’re currently witnessing isn’t the death of “the music industry,” but rather the decline of a particular music-related business model and the firms that were built around that business model. A few people will still get rich, and I’ve got no objections to that. My point is simply that if fewer people get rich making music than they did in 1990, that’s not a public policy problem.

Until the long-playing record became standard, most of the money in the music business came from sales of sheet music, and live performances. That’s why songwriters and bandleaders used to be celebrities on a par with singers.

The sheet music was for in-home performance by amateurs. I wonder if there is a market for karaoke MP3s, or MIDI files that will let the home user replace the lead guitar track with himself? “Guitar Hero” is a lot like that already.

You’re right.

I read your post to say “the state should treat music as a hobby, like dancing and tennis, and not interject”, which sounds wrong to me. I just meant to say that some public policy – copyright, mainly, though preferably not the bad U.S. kind – is needed.

Bands make their money touring…

I don’t entirely agree with the comment that “the decentralizing power of the Internet is now returning us to the historical norm, which was for music to be primarily a hobby like tennis or dancing.” There’s still plenty of work for professional musicians. It just isn’t the sort of work that contains the faint promise of one day being a star. (Although, since it’s easier than ever to put out your own music independently, the chances that someone who works as a studio musician, wedding band bassist, or cantor will also attract a cult following on the side are now much higher.)

There’s still plenty of work for professional musicians. It just isn’t the sort of work that contains the faint promise of one day being a star.

But this is true of tennis and dancing as well, isn’t it? People make money giving tennis lessons and coaching tennis teams. And a tiny minority make a living playing tennis for spectators, endorsing products, etc. Same story for dance: there is a large number of dance teachers and coaches, and a smaller number of people who make a living giving dance performances.

There will still be a lot of people who make a living from music. There just won’t be an arbitrary, technologically imposed barrier between “professional musicians” who earn a living by selling their music to a nationwide audience, and the much larger universe of people who lack access to that distribution network and so can’t make a living by selling copies of their music.

Sure, it’s true of tennis and dancing as well, though the dynamic isn’t exactly the same. I’m just noting that this isn’t just a matter of music largely retreating to amateur status while a few stars soldier on; that there’s also an intermediate professional world that analyses of the future of music often leave out.

An astute point!