I recently had the pleasure of reading The Great Stagnation, Tyler Cowen’s excellent “Kindle Single” about the future of innovation and economic growth. Cowen makes the case that, contrary to the right-of-center conventional wisdom, the American economy is in the midst of a decades-long period of mediocre economic growth. Previous generations of Americans enjoyed an abundance of “low-hanging fruit”—cheap land, technological breakthroughs like electricity and the internal combustion engine, rising levels of education, an end to racial and gender discrimination—that allowed rapidly increasing living standards with relatively little effort. But now, he says, the orchard is getting bare. Since the 1970s, big innovations have been few and far between, and this explains the comparatively slow rate of GDP growth in recent decades.

The obvious response is to point to Silicon Valley, where there’s clearly a lot of innovation going on. Cowen anticipates this objection in his third chapter and argues that the IT revolution is overrated as a source of economic growth. Drawing on a previous book, he argues that the Internet is great for “those who are intellectually curious, those who wish to manage large networks of loose acquaintances, and those who wish to absorb lots of information at phenomenally fast rates.” But, he claims, there’s less there than meets the eye. Most people don’t spend enough time on the web for it to significantly improve their standard of living. And in any event, blogs, Facebook and Twitter don’t create jobs or produce revenue for the government, which means that we can’t count on them to drag us out of our current fiscal predicament.

By focusing on “the Internet”—and specifically Facebook and Twitter—Cowen trivializes an industry whose economic effects extend far beyond a few overhyped websites. And Cowen fails to appreciate that information technology innovations have a different economic character than the innovations that drove economic growth in the 20th century. It’s true that software innovations often make a relatively small contribution to measured GDP. But this this is less a reflection of a “great stagnation” than a sign that official economic indicators are a bad way to measure our generation’s low-hanging fruit.

To understand what makes software-powered innovation distinctive, it helps to contrast it with the industrial-age innovations that proceeded it. For most of the 20th century, innovation was embodied in physical products like cars, televisions, washing machines, and airplanes. This style of innovation is relatively easy for government statisticians to deal with. If an economist at the BLS circa 1961 wanted to know how much the television industry was contributing to GDP, he simply added up the prices of all televisions sold to consumers.

Of course, economists aren’t only interested in measuring national output at a single point of time; they want to measure how the standard of living changes from year to year. If total spending on televisions falls, statisticians need to figure out whether this is because consumers are buying fewer televisions or because televisions are getting more affordable. The distinction is crucial because the former represents a decline in national output, while the latter amounts to an improvement in the standard of living. And of course, economists have to be careful about making apples-to-apples comparisons. For example, the switch from black-and-white to color pushed up average television prices, but it would have been a big mistake to record this as a sign of televisions in general getting more expensive.

There are many important subtleties to measuring changes in economic output, and official statistics have tended to overstate inflation (and hence understate growth rates) to some extent. But the important innovations of the industrial era had some common features that made such problems manageable. They came embodied in discrete physical objects with a fixed feature set. And the value of new innovations was roughly reflected by the prices consumers were willing to pay for them. If consumers were paying twice as much for a 60-inch television as a 40-inch one, it’s reasonable to infer that the former is twice as valuable.

Now imagine an alternate universe in which industrial products did not work this way. Suppose we lived in the world of Harry Potter, and one day in the late 1950s RCA hired a wizard to wave his magic wand and transform all of the world’s black and white sets into color sets. This would clearly represent a large increase in the standard of living—a larger increase, in fact, than the non-magical process whereby people have to buy new, more expensive, televisions. Yet the government in the alternate universe would almost certainly have recorded a smaller increase in GDP. Our own BLS would see consumers buying more expensive televisions while in the Harry Potter universe consumers would be happy with the old, cheap ones. Hence, consumers circa 1970 would be wealthier in that universe than in ours, but official GDP statistics would show just the opposite.

Today these magic wands exist. For example, a couple of years ago, Google waved a magic wand that transformed millions of Android phones into sophisticated navigation devices with turn-by-turn directions. This was functionality that people had previously paid hundreds of dollars for in stand-alone devices. Now it’s just another feature that comes with every Android phone, and the cost of Android phones hasn’t gone up. I haven’t checked, but I bet that this wealth creation was not reflected in GDP statistics. And it’s actually worse than that: as people stop buying stand-alone GPS devices, Google’s innovation will actually show up in the statistics as a reduction in GDP.

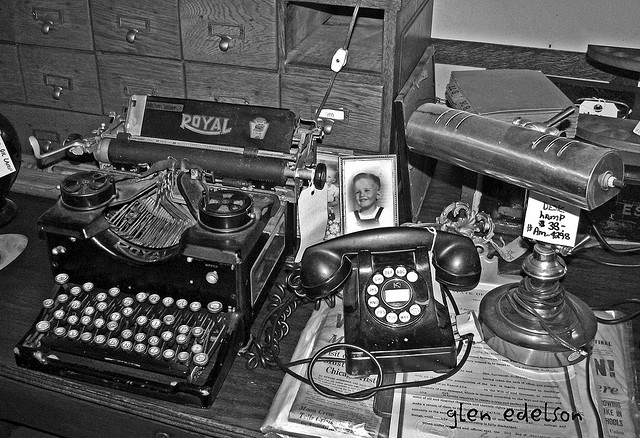

Cowen writes that the Internet is producing wealth that “is in our minds and in our laptops and not so much in the revenue-generating sector of the economy.” This isn’t exactly wrong, but it fails to appreciate the extent to which the software industry is entangled with the “revenue-generating sector of the economy.” The digital revolution isn’t just introducing novel ways to amuse ourselves, it’s rapidly displacing a wide variety of “revenue-generating” products and services: typewriters, newspapers, magazines, books, maps, cameras, film development, camcorders, yellow pages, music players, VCRs and DVD players, encyclopedias, landline telephones, television and radio broadcasts, calendars, address books, clocks and watches, calculators, travel agents, travelers checks, and so forth.

Paul Graham and Reihan Salam have been popularizing the term “ephemeralization”, originally coined by Buckminster Fuller, to describe this process whereby special-purpose products are replaced by software running on general-purpose computing devices. As the list above suggests, ephemeralization is affecting a growing fraction of the economy. And with technologies like self-driving cars on the horizon, its importance will only grow in the coming decades.

Ephemeralization offers an alternative explanation for the puzzling growth slowdown of the last decade. Every time the software industry displaces a special purpose device, our standard of living improves but measured GDP falls. If what you care about is government revenue, this point might not matter much—it’s hard to tax something if no one’s paying for it. But the real lesson here may not be that the American economy is stagnating, but rather that the government is bad at measuring improvements in our standard of living that come from the software industry.

In some ways, I’d rate the effect as larger than you imply, my phone replaces gps/maps, mp3/walkman, hand held gaming device (gameboy, etc), organizer, camera, ebook reader, and various other bits of paper/books. Granted, I’ve never owned a hand held gaming device or gps ($65 map books), but I’ve owned quite a few newton/palm devices, and at least one of each of the others, my phone is a better device than any of them at their function. It also reduces my desire for a small laptop (I have a big one, but I don’t feel as much of a need to have it with me now).

Well stated Tim.

I believe the “ephemeralization” process goes beyond increasing quality of life through providing more functionality without added cost; by concentrating more and more capabilities into a single device, it allows one to simplify their life by reducing the number of physical objects they feel compelled to own. This reduction of physical possessions can have all kinds of positive effects on quality of life, not least of which is the positive psychological effects that simplification affords, which would obviously be difficult to quantitatively measure.

Still you can’t eat or drink software, and burning old CDs and floppies in your fireplace for warmth isn’t recommended. The proper concern of economic policy remains measurable productivity and physical living standards. (Price-level adjusted, to be sure.)

Cloud computing, as an example, is of interest to the extent that it increases efficiency and reduces costs — and this is determinable by normal accounting methods. Wow, look at how this quarter’s IT expense went down compared with fiscal 2010. We’re more competitive, let’s reduce our price enough to sell more units while still increasing marginal profit. Decisions of this sort get picked up in those economic sampling stats that measure both unit output and cost/price per unit. (Once again, historically adjusted in the GDP numbers. Let’s say increased efficiency even results in deflation or at least reduced inflation. This could hardly escape notice. And if increased efficiency doesn’t find itself reflected in price then corporation profits will skyrocket and corporate tax revenue should go up — and, just maybe, the Antitrust Division ought to take an interest.)

Anyway, imagine that Dan Nocera and his MIT-based team actually make hydrogen bond energy freely available by replicating photosynthesis. His final paper is awaiting completion of the patent process and there’s already a Tata-backed pilot project afoot in India. A lot of current concerns may prove to have been ephemeral. To be replaced however by what unforeseen issues?

Excellent points, Tim, particularly about Ephemeralization.

I’m ashamed to say that I didn’t immediately realize how badly Cowen was trivializing the IT Sector by focusing on a handful of software companies, when it is so much vaster than that. Everything from Cisco to Microsoft is involved in that sector, along with all of the employees providing IT services (including people for whom it’s not their main job). While the individual companies don’t employ the gigantic numbers of employees that you saw in some of the old industrial firms, altogether the sector is vast.

I think that’s missing the point, though. We don’t necessarily need the “tangible goods” sector to be huge, not when productivity is so high. Just look at agriculture, where it’s extremely productive – and extremely small compared to the rest of the economy.

And when the People’s Liberation Army comes ashore at Long Beach, California, we’ll make a really awesome Facebook page about it, right?

@ Brett: Agreed. Suppose tangible good production shrinks to 10% of today’s economy (a conservative estimate), and the rest of current economic activity is ephemeralized. How do we manage the transition to a world where 90% of our current economy is no longer monetized? Or perhaps is monetized on some radically different basis?

@Nick M: Interesting reference to Nocera. So maybe much of that remaining 10% would get internalized to communities and even households. The energy and most materials can be sourced locally — from the air and sun, even — while a lot of recipes will be freely available.

@ Don Marti: Tell that to Mubarak’s troops. Or to Ho Chi Min’s. Superior intelligence (in the military sense) and coordination can beat more weapons in most circumstances.

More generally we’ll certainly see a lot of fear mongering about this transition. And fear mongering often works given the cognitive defects of humans. But it almost never helps to shape useful policy, it just serves the interests of the mongers.

@Don Marti

You’re still confusing “small, heavily productive industry” with “no industry/de-industrialization”. That’s why I brought up the example of the agriculture sector, where its overall value has grown along with productivity, but it’s a small part of the economy relative to the size of the rest of it both in terms of output and employment.

On the military point specifically, it takes a lot longer to churn out military equipment than it used to. Your army is going to be running off of a stockpile of parts and equipment anyways.

@Jed Harris

Realistically, we’ll have different measures by then to analyze GDP and living standards.

I’m not sure how we would get to anything resembling 90% ephemeralization. That would be the equivalent of having high-level artificial intelligence and heavy robotics doing most of the work in society. My guess (and this is a guess) is that costs for goods and services would be so low that our living standards would be higher, even if the actual inflation-adjusted number that is our median income is lower.

Outstanding post.

I have used each and every thing on your list (newspapers, magazines, etc., etc.) and with the single exception of the DVD player (now replaced with BluRay.. oh! Blade Runner on a 60″ DLP on BluRay!) I don’t use -any- of them.

How’s this for technology:

1) I was working from home in Los Angeles calling London over my wifi using a software-based IP phone on my laptop (summarized below).

2) I just set my 11-year old daughter up with Google Voice. Now she can text and call me for free. Oh, she doesn’t have a phone — just an iPod touch with wifi. This is a significant gain in my quality of life.

Very simplified technology steps during my call from Los Angeles to London:

1) A headset converted my voice into an electronic signal.

2) My laptop sound card digitized signal from the headset.

3) The sound card hands a digitized stream to IP phone software.

4) VPN software encrypts the stream and hands it off to wifi hardware.

5) Wifi hardware encrypts the stream again and sends it to my wifi router over the air.

6) My wifi router decrypts the signal and hands it to my DSL modem which is in contact with my ISP.

7) Using the destination address provided in my VPN software, my ISP ‘somehow’ gets the encrypted stream to my company’s VPN server in real time.

8) VPN server decrypts the stream and hands it to the IP phone server.

9) Knowing which internal number I dialed, the IP phone server sends it back to the VPN server to be encrypted (again) and sent (again, ‘somehow’ by our company’s ISP) across the Pond to our London office. (It might actually take a path through our data center in the Midwest, but that’s not critical here.)

10) Another round of decrypting, IP phone server routing, and passing across local LAN routers to the exact phone I dialed.

Bonus — We were doing a screen-sharing session at the same time.

Bonus 2 — Nearly every technology listed (hardware and software) was designed by separate, competing companies.

No one noticed any of that was happening. The call was perfect. The very idea that someone thinks internet technology advances have basically given us web surfing and Facebook is astonishingly naive about what’s really going on. (Multi-billion dollar industries are being completely reorganized, if they’re surviving at all.) Such a viewpoint is as misguided as a worry about things marked

Sorry… bad href tag there.

… things marked “Made in China.”

http://abcnews.go.com/Business/made-america-smithsonian-promises-sell-american-made-souvenirs/story?id=13087867

@Brett:

I sure hope so. However I’ve looked around and don’t currently see any good candidates.

One place where this would make a huge difference is in evaluating government expenditures. Another is in monitoring the positive and negative externalities from various activities.

An important example of a positive externality: the social benefits of media “piracy” (highly relevant to this blog). We should be able to compare benefits of “piracy” to the costs. But we can’t, because we don’t have any metric. Our lack of a consensus metric for these benefits empowers aggressive rent seekers in that domain, because they can claim dollar losses.

Agriculture fell from over 50% of the economy to less than 3% in the last century. Most of the decline occurred in the 1930s and early 1940s.

Industrial employment in the US is falling, but industrial production in the US is rising at a good clip. (Increased manufacturing productivity is the big driver, not offshoring or “hollowing out”.) If this trend continues, industrial production will be significantly less than 10% of our economy in the not too distant future.

So adding up these trends, agriculture and manufacturing end up less than 10%. And everything else is already pretty darned ephemeral.

@Jed Harris

I disagree with that. The Services Sector has many areas that aren’t easily “ephemeralized”, particularly in the positions where the job isn’t oriented around a repetitive, rules-oriented set of tasks.

We still have one major metric for standard of living which (rather strangely, in my opinion) hasn’t been considered: unemployment numbers.

I think it’s hard to dispute that whatever improvements the software industry brings to our quality of life, they’re disproportionately skewed toward higher income classes. That wouldn’t be so bad, except that as you say ephemeralization is bad for “traditional” industry. It’s increasing the number of people in the lower income classes, while providing them fewer benefits than anyone else. And all the while, technology makes human labor more efficient, decreasing the demand for it. It’s been decades since we even made full employment a policy goal: it seems to be accepted that we don’t need everyone in the workforce.

What isn’t really clear is what those people are supposed to do. Should they just subsist forever on welfare, until conservatives decide they’re leeching our money away and cut off the flow? Turn to crime? I don’t know.

If we have to move toward an economic model where success isn’t measured in GDP, then fine. If it showers us with minor and major conveniences that would been unimaginable in the past, and allows us unimaginable amounts of leisure time, fine. (I don’t see why we couldn’t move to a thirty-five hour work week like some other countries, for instance, with so many people available to pick up the slack). But before we can call this a period of prosperity for America, we have to find a place in our society for twenty-eight million Americans.

Marshall Brain, a few years back, also had some interesting things to say about this topic, more from the perspective of smart robots http://marshallbrain.com/robotic-nation.htm

“Decisions of this sort get picked up in those economic sampling stats that measure both unit output and cost/price per unit.”

Do they really though ? Look at Apple. They don’t reduce the price of their iPods, they simply add features and keep the price point the same. The same thing happens with other computer components. Look at RAM or hard drives, the price points have gotten to the point where they are fairly stable, but you are constantly getting more value at each particular price point.

@Brett:

An important question. I don’t know of anyone who’s done a good economic analysis, but I’d love to see one.

The reference to Marshall Brain is interesting, I haven’t had time to evaluate it in depth. However he doesn’t seem to tie his argument back to economic statistics.

Driving would seem to fit your definition. It is somewhat repetitive, but the world is always throwing new problems at you, and there’s no imaginable rulebook that would tell you how to handle all of them. And if we do define driving as repetitive and rule oriented, then a huge proportion of the economy fits under that umbrella.

But driving is well along the way to being automated. So that’s a major area of services that could shrink drastically over the next ten years. The stuff we need to add to cars and trucks in place of drivers is quite ephemeral (sensors, computing power).

Anything that involves processing paper can be largely automated. Checkout clerks are already being automated away. Moving goods around and taking inventory seems like an obvious candidate for elimination; that’s a big one. If we can automate driving, I’m sure we can automate hair cutting, baristas and bar tenders (though people may pay just to have a human to talk to). My doctor has already been 50% replaced by automated lab procedures. Yoga instruction and psychotherapy will be harder.

One way to approach the broader question would be to make a list of occupations that (1) make up a significant part of the economy (say all together at least 10%) and (2) we think won’t be automated. Maybe such a list exists, but I haven’t seen it.

Then we could track it for a few years and see if it holds up.

The cheapest new car you can buy today may cost much more, adjusted for inflation, than the cheapest car of 1981. However, the cheapest car of 1981 didn’t have air bags, ABS, FM radio, power windows and doors and dozens of other little safety and convenience features we don’t even notice.

However, if I wanted to buy a car with those features today, you couldn’t do it at any price, unless I got a depreciated used model, which isn’t really the same thing at all. I may appreciate the airbags, but my costs have not gone down.

Similarly, every time I buy a new phone, I spend about the same amount of money every couple of years and get tons of new features (at least some of which I appreciate) but the bill in my hand as a I walk out of the store doesn’t vary all that much. If I take the free phone, I still need to buy a plan. Again, more features, same cost, very limited options if you want less.

Oh, and those things that can’t be made ephemeral – like the house I live in and the food I eat – aren’t getting any cheaper either, even if they are somehow improved. I’m paying the same and getting more. But what if I’m an “ephemeralized” journalist, got laid off from a job that provided a middle-class salary and became a blogger working the same hours in exchange for a little ad revenue?

And the fact that you can get turn-by-turn directions to a soup kitchen? Nice, but it misses the point that I’ve been made surplus to requirements.

There are winners and losers and no amount of techno-utopianism from libertarians will change that. Instead of the “welfare queens in Cadillacs” argument we had in 1980, we have “but poor people have cell phones!” The staples of a decent life in the developed world (housing, food, energy, transportation, education and piece of mind from basic financial stability) haven’t been “ephemeralized” or gone down in price over the last few decades, but a lot of people have been made redundant. “Let them eat Skype” is not an answer.

@Ryan:

Employment / unemployment is a very important touchstone for these changes. But it also illustrates the problem with measuring value in money.

If we spend time finding music online, or (as here) participating in an online discussion, or writing articles on Wikipedia, or in the future downloading designs for household goods and making them on our 3D printer, are we spending time in “leisure”? Or “unemployed”? Or “unpaid labor”? Or what?

And critically, how should the time we spend be valued?

In many cases time spent doing things for ourselves is economically more efficient than paying someone else to do them. But to the extent activities become demonetized, they become invisible to current social accounting, and the increased efficiency doesn’t show up anywhere (except as “hedonic adjustments” which is the attempt by economic statisticians to answer TBW’s point — but those are pretty weak).

It seems obvious that it is wrong to say (as we do now) “Only the activities where you earn or spend money count toward social value.” But what should count, and how should we weight any given activity ?

I don’t have an answer. But it bothers me that in many cases we aren’t even asking the right questions.

Tyler Cowen seems complete unaware of or uninterested in this problem in The Great Stagnation, and Tim is absolutely right to focus on this issue in his comments. As Tim says,

And I’d go further and say that going forward, many innovations will produce a net decrease in GDP, and collectively they are likely to add up to a large decrease.

” But what if I’m an “ephemeralized” journalist, got laid off from a job that provided a middle-class salary”

These people exist — but there also exist people whose job is only made possible because that same new technology which lets them do their programming job 1000 miles away from their employer — like me.

“These people exist — but there also exist people whose job is only made possible because that same new technology which lets them do their programming job 1000 miles away from their employer — like me.”

I doubt that is happening at a 1-to-1 basis. It’s not a new problem, either. Industries have been swept away by technological change as long as there has been industry, causing real suffering and displacement, as well as new jobs for different people. The difference here is the denial that there is any problem at all by juicing the stats with ephemeral benefits of technology.

A large population with nothing to do can’t be sated by watching torrents or playing Angry Birds all day.

Sorry if I bring up some of the same points earlier, but dont have time to read all of them. I am a partner in a software/consulting firm that could not have existed 10 years ago. The internet allows us to develop, market, and sell a range of solutions that 1o years ago would have required 20 people and significant capital infrastructure. We have 4 full time “employees” and work with many parnters and consultants that provide us a global presence. We were able to weather the “great recession” easily as our operating expenses are minimal, we have no debt, and are able to adapt very quickly to changing market conditions and opportunites all because of the “intertubes”. Many of our clients are absolutely stunned when they discover how small our core group actually is, but they never complain. Due to the efficiencies and flexibility that the internet provides, we are able to provide solutions to our clients at a fraction of the cost of our competitors. I doubt that much of this value is captured in GDP calculations.

“Due to the efficiencies and flexibility that the internet provides, we are able to provide solutions to our clients at a fraction of the cost of our competitors. I doubt that much of this value is captured in GDP calculations.”

Why wouldn’t it be? Businesses providing new or better services for less money is the history of capitalism in a nutshell and the main driver of GDP growth as long as we’ve been calculating that statistic. GDP doesn’t just increase when someone works one more hour at the same job.

If new tech is replacing old, taking it out of the GDP figure, wouldn’t that consumer surplus show up in demand elsewhere?

This type of arguments are so self-serving. It goes like this: Because technology is so great it must improve in a noticeable and meaningful way our standards of living. Since this improvement is not reflected in GDP figures, those GDP figures must be wrong. They assume what must be proved.

This is one of the core theses of Cowen’s book, and he explores the idea more thoroughly in “Create Your Own Economy.”

He is not always clear, though, about what “economics” is. It’s not the study of money and “stuff,” it’s the study of utility and well-being–or, even better, “wealth,”–with money and stuff being the best way to approximate that. (It’s amazing how few people recognize that “wealth” is a purely mental phenomenon; this is how the free exchange of goods creates wealth in the first place.)

Thus, it’s not correct as I see it to say that the “economy” is stagnating if wealth is growing. Such statements should be qualified–the “money economy” is stagnating, etc.

@Schisma Tism

The process of ephemeralization could actually shrink the dollar economy. It’s not clear there will even be any net consumer surplus.

The stagnation hypothesis does not even make sense on its own terms. Fossil fuels augmented human capacity for work (food energy converts to work and now so does coal, oil, etc.) . Computer technology has now augmented human capacity for thought (computer processors make computations far more quickly than our puny brains can). Both shift the production possibility frontier in basic fundamental ways. We are not stagnating, but growing in a different way.

@rj

I’m not convinced that’s true. Our ancestors probably would have wondered at our ability to waste spare time, when they were working 12-hour days.

In my own situation, I know that there are a lot of things I could and would do if I could live comfortably with a very small number of hours worked.

Juan, the argument gives a concrete example of an improvement not reflected in GDP figures. What more do you want?

I agree with the general thrust of this very good post, but the fact that more and more wealth is untaxable seems *very* important to me. This also seems likely to further shift the balance of economic power toward those who own capital that contributes to the physical necessity baseline that every person still has to pay for. The virtual pie is getting bigger, and that this comes at a cost to the size of the physical pie is probably okay. But people are invested to varying amounts in those different pies, and it seems like this has the potential to cause some pretty serious problems.

that money doesn’t measure value, bucky had some ideas about that, as well.

@Jed Harris:

I agree with you that these are important questions, if you’re interested in developing better and better economic models. Yes, this time has some value, and it would be nice to quantify it.

My concern is that, with more nuanced models still undeveloped, we might allow these musings to blind us to some obvious and important truths. Specifically, in this case, the fact that in our current society and for the foreseeable future, the time we spend looking for music or posting blog comments cannot remotely compensate for not having a job. It would be nice to demonstrate this quantitatively, but at this point the burden of proof cannot possibly be on my side.

And at the risk of misinterpreting you, I don’t think you’re seriously arguing this point. Compared with fun mental exercises like radically rethinking the way we spend our time, it’s just too mundane, so it looks like you moved on to something more interesting. I wouldn’t dwell on it either, except that I think it’s been overlooked.

How else can we explain the article’s conclusion?

Yes, the employed people (and middle/upper income classes in particular) are probably seeing an increase in standard of living which hasn’t been accounted for. But 9.2% of employable Americans and their families have problems that vastly outweigh this. Any hypothetical measure of economic well-being which would say “Our economy is actually in pretty good shape, thank you very much,” is critically flawed on some logical or ethical level.

(You can argue that ALL such metrics are somewhat myopic. And I wouldn’t raise a stink if GDP were going up and we called this a measure of “prosperity,” with the understanding that GDP isn’t a function of unemployment rate. But you can’t daydream about a hypothetical perfect metric of “stagnation” which takes all standard-of-living factors into account, and then have it exclude a tenth of the population’s well-being.)

This is only concerning because it’s already too easy for the more fortunate of us to forget that other Americans are suffering. I’m no banking executive (~$40K salary) but the situation looks fine from where I’m sitting, and if I read less I would be very susceptible to the idea that everyone’s really doing all right.

@John:

I agree with John but mostly I don’t think economists actually study well being independent of money. (I should note that economics is actually about how to allocate scarce resources to maximize well-being, not just well-being in general.) Cowen seems reluctant to shift focus from money to well-being. He summarizes his thinking about the internet (and I guess ephemeralization more generally) as follows:

So Cowen feels a need to treat the “revenue-generating sector of the economy” as special. He doesn’t seem to have any model of how, as a society, we can make economic tradeoffs without money — though if he’s right about his overall thesis, that’s a very important question. He doesn’t propose a metric for social value other than money, or even seem to notice the question — which again is very important given his thesis. At one point he converts some “fun” on the internet into $20 without any discussion of how we assign dollar values to “internet fun”.

I also agree with Tim that Cowen is trivializing the internet by emphasizing “fun”. For example, online discussions and wikis permit people with rare or complex diseases to learn how to manage them better than their doctors in many cases. This simultaneously increases their quality of life, improves their medical outcomes, and reduces costs. Focusing on “fun” greatly understates the value of online resources. But we have no way to measure that value and thus no way to quantitatively factor it into our social tradeoffs.

* There’s no apparent way to cite a location in a Kindle book. Quoting one is hard. Generally the Kindle format will be bad for discussions of eBook content. So not all ephemeralization is value enhancing, even if it is economically very successful.

@ Ryan:

Totally agree, didn’t want to imply otherwise. Things are not OK. Unemployment is an important symptom, but far from the only one.

My point however is that we don’t know how to deal with these problems partly because we can’t measure what’s actually happening to the economy. (This is more or less consistent with Cowen’s analysis, but it seems like the only solution he can imagine is to get more activity back into monetary terms. And I don’t believe that’s going to happen.)

As a society we should organize things so everyone has a decent base level quality of life. Given how rich we are this doesn’t seem like much of a stretch.

The historical solution is to provide a “safety net” — directly allocate enough stuff to everyone so they can live OK (which these days would include good internet service). But this makes people subservient to political “generosity”.

I hope there is a more decentralized, bottom up solution. I’m fairly sure if we take that as a goal we can find one.

But however we address this problem, we pretty clearly need to think about measurement and allocation of social resources in ways that go well beyond their monetary exchange value. Money is just not a good enough metric (by itself) anymore.

As a poor person (bottom 0.5% of the economy, although i work full-time) who lives in the countryside, with intermittent/usually no phone signal, i can honestly say that said devices are unaffordable and pointless (no signal=no point). They’re not adding anything to my quality of life, and they couldn’t – if i search for local Wales information, all i get is crap about Los Angeles, London and New York. I feel their main contribution is to create a sort of parallel universe of people who take part and those who are excluded. (I’m not sure how many are excluded, but i use the internet almost solely to follow the news and study, whereas most people i know are interested in neither so do not use it.) I nevertheless agree that sales of traditional items are down here and among people like me as much as among the included, because we think ‘they won’t last’ ‘no point buying it, save up for a computer’ etc. Therefore manufacturers lose even their traditional elderly/rural/poor customer base (those customers are always the most old fashioned and the last to switch – the ‘last-adopters’ so to speak).

Information is an important factor of STEMI analysis (Space, Time, Energy, Mass, Information) and through a modern alchemical equivalent exchange can effect the other STEMI factors.

Information (an identity* difference that makes a difference) = working smarter rather than harder = more wealth.

* A bit Randian here.

No, not REALLY. A 60-inch television is worth twice as much money as a 40-inch one. It’s NOT twice as valuable. Right?

Wristwatches have been ephemeralized (Dick Tracy’s wrist radio notwithstanding) to mere adornment. Clocks, less so.

Cowen quite misses the point(s) regarding computers AND the Internet. Just look at what I’m doing right now, utterly without benefit of postage stamp.

I post this quote and link not so much in response to the blog itself, but some of the comments lamenting the unemployment that arises from innovation.

Henry Hazlitt, Economics in One Lesson

“It is no trick to employ everybody, even (or especially) in the most primitive economy. Full employment -very full employment; long, weary, back-breaking employment-is characteristic of precisely the nations that are most retarded industrially. Where full employment already exists, new machines, inventions and discoveries cannot-until there has been time for an increase in population-bring more employment. They are likely to bring more unemployment (but this time I am speaking of voluntary and not involuntary unemployment) because people can now afford to work fewer hours, while children and the over-aged no longer need to work.”

http://fee.org/library/books/economics-in-one-lesson/#0.1_L8

C0lor TVs are a bad example. As I remember it (I was around at the time), the initial consumer-grade color TVs were not a “large improvement in the standard of living.” They were muddy, and the reds were over-saturated and tended to bleed. B&W TVs just delivered a better picture. I only really started to appreciate color TVs when Sony brought out the Trinitron, which really was a startling improvement (in the sense that the minute you saw one, you wanted one).

The original color TVs were a novelty, and did appeal to some as status symbols, which led to others (like my father) laughing at them behind their backs for buying such an overly expensive piece of crap.

And I should mention that there are those who think that the TV represents a decline in the standard of living, because it’s addictive and diverts people from more useful activities, but arguments like that don’t seem to fit into economists’ world-views.

Does it matter that the ’empheralizers’ of Google and Apple have extraordinary stock value and this is (I think?) represented in GDP statistics?

There’s also an interesting Marxian angle here. For example, Kauffman is arguing for increased liberalization in order to sustain the growth of these crude measures like GDP (http://www.kauffman.org/newsroom/economic-growth-hinges-on-frontier-economics-of-entrepreneurial-upstarts-and-reduced-government-intervention.aspx). Ironically, they use a Marxian term, ‘frontier’ – capital needs to find new sources for growth, weather that be microfinance, as Roy argues in her excellent book Poverty Capital, or in lessening government regulations on, say, collective bargaining or environmental protections. Ephemeralization adds an interesting twist.

Kevin, I don’t think equity prices are counted as part of GDP. And in any event, equity prices are a function of expected future profits, which is distinct from the consumer surplus they generate.

Progress: Moving beyond scarcity towards an abundance of resources.

It has always been abundance that give us peace, freedom, innovation, and individual autonomy.

Combine abundance with purpose and you will get enlightenment,

Combine abundance with necessity and you will get innovation.

Interesting argument, but I was expecting you to go elsewhere in it.

First of all, this claim: “…as people stop buying stand-alone GPS devices, Google’s innovation will actually show up in the statistics as a reduction in GDP” is only true if you hold all else constant. What are the chances of that being a realistic assumption? (Hint: If history is any guide, not very good. Typically innovation, if it results in a revenue loss in some portion of the macroeconomy, still produces a net gain overall.)

On the other hand (and this is the argument I think you ought to have explored)—history may not be a good guide in this case. Maybe ephemeralization will lead to a techno-dystopia where robots do all the work and everyone is unemployed and starving (good luck with that one). More realistically, ephemeralization may be proceeding at such a rapid pace that labor is having a harder time adjusting then it has in the past, resulting in some of the pain we’re seeing in the economy.

The trouble with this line of argument is that whatever effect ephemeralization is having on growth, I suspect it pales in comparison to the stagnation we can account for by looking at our economic policies. But perhaps I’m wrong and the effect is in fact non-trivial by comparison.

Or, perhaps more interestingly, there’s an argument here about what the cultural implications of “ephemeral-sector” jobs replacing “non-ephemeral” ones might be. (Fewer lawyers is almost certainly a good thing, but the ongoing brain drain in journalism is disheartening and do we really need so many people doing search engine optimization?)

But now I’m just rambling.

Thanks for the thought-provoking post!

Very interesting piece, I think your example re: turn by turn navigation is excellent (I also liked the Harry Potter universe/magic wand illustration as well). An additional example, which I believe the first commenter mentioned is digital cameras. Many people are finding that the quality of the digital camera on their mobile/smart phone is good enough to at least replace the digital camera they purchased several years ago, and some are finding that its good enough to keep from buying a new one. This trend has been linked to the recent demise of Flip, although there was obviously more to the closure of Flip (like Cisco a historically non consumer/non retail company deciding to purchase an exclusively consumer/retail company/product) which as you suggested with GPS devices would show up as a decrease in GDP despite an increase in the quality of living (now I ALWAYS have my camera with me, and can capture many more important moments in my life).

You’re completely misunderstanding what wealth is. It’s not what you have, it’s what you can choose to buy. If a dedicated satnav used to cost $200, and all of a sudden our phones magically do the same thing, that doesn’t mean we’re all $200 better off. If you have a spare $200 you can choose whether to pay someone to fix the plumbing in the bathroom or paint your fence with it, or spend it on a glitzy toy like a satnav. Suddenly having that ability for free does nothing. If Google had magically apparated a million skilled plumbers and electricians out of thin air (who didn’t need feeding, or somewhere to live, or need to be paid) then yes, that would be some achievement, but suddenly adding a new feature on your phone, that’s nothing. Less than nothing. It quite rightly has no impact whatsoever on GDP (other than maybe reducing it, if all the people who previously worked at the satnav factory and generated export revenue and earnt good money which they spent on other goods and services are now unemployed).

rolf don’t be a buzzkill. let the ‘architects’ keep thinking they’re not tools to undercut labor’s negotiating power.

You are wrong about the way your government is measuring GDP. You need to look into Substitution and Hedonics and the effect that has on inflation and GDP numbers.

http://mises.org/daily/1873

http://seekingalpha.com/article/24933-substitutions-and-hedonics-inflation-data-absurdities

lqz: Those articles don’t make much sense to me. It seems obvious that quality changes are relevant to inflation calculations. If average prices are rising because people are buying more up-market versions of some product (more Lexuses and fewer Camrys), it’s a mistake to count that as evidence of inflation. Obviously, reasonable people can criticize the specific way the BLS does it, and it’s possible that the BLS is currently over-doing it. But Mueller seems to be objecting to the very concept of taking quality changes into account, which is obviously wrong.

I love the concept of ephemeralization. It is wonderful. But a better computing device or cell phone or mobile computer of any kind is not wealth itself, it is the product of investment. I still think that we have abandoned manufacture in our “advanced” culture at our great peril. I believe, with Hamilton, that the key to a healthy nation is the wide array of jobs, all of which owe their existence to manufacture. Not everyone can be a worker in intellectual property. It is not good to aim at that anyway. Investing in one’s own countrymen by creating manufacturing facilities creates far more energy than the mere intellectual effort behind creating the software. It creates jobs for the rest of us. Right now, we’re creating jobs in China, which is cheaper for us, but still is giving China the great advantage of being able to make the tools for tomorrow. They’re growing. We’re shrinking, no matter what you say.

No need to agree with the author. Only trying to point out to you that your government is taking into account quality changes when it comes to the inflation and GDP numbers it puts out. So it is wrong to think that it has gone unnoticed that phones can now be use as GPS devices. They do take such things in to account, so that part of your premise is wrong. Not that I think that makes Tyler Cowen right, http://arstechnica.com/business/news/2011/05/intel-re-invents-the-microchip.ars .