My post last week about immigration as a civil rights issue generated a fair amount of discussion. There were a number of critical comments here and at Will Wilkinson’s blog. One objection was to my use of the term “civil rights.” I think the term fits, but if it makes my argument clearer I’m happy to stick with the more general term “human rights.”

When I argue that immigration is a matter of human rights, my point isn’t that a nation is morally obligated to give immigrants all the rights and privileges that American citizens enjoy. There is a variety of plausible reasons a nation might have for regulating the movement of persons, and there are obviously some benefits, including the right to vote, that can be properly reserved to citizens or to permanent residents. I was making a narrower point: that immigrants, legal or otherwise, have rights that the US government is morally obligated to respect. And that there’s something deeply offensive about the premise, reflected in a lot of mainstream discussion of immigration issues, that the rights and welfare of immigrants is irrelevant, or close to it, in thinking about immigration policy.

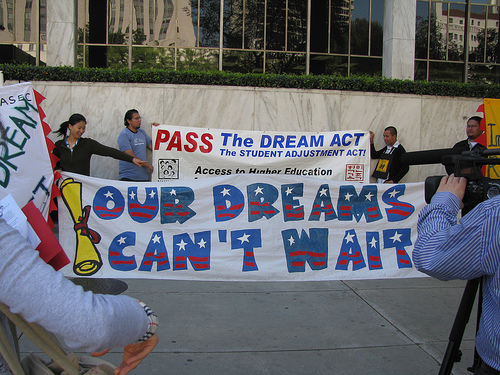

Consider this sentiment by self-described liberal Tod Robberson, discussing the DREAM Act, which would provide green cards to kids whose parents brought them here illegally while they were minors:

I want to be fair to kids whose only crime was to accompany their parents to the United States and who, in many cases, know no other country but this one. But at the same time, I’m not sure it’s a smart move to open the way for potentially millions of college-educated illegal immigrants to start competing for precious jobs against college-educated American citizens.

I don’t want to get into a semantic debate about whether this perspective is “racist” or not. But I think it demonstrates a kind of crude parochialism that’s morally objectionable for some of the the same reasons that racism is problematic. The kids whose lives would be transformed by the DREAM Act are, we should remember, Americans in every relevant sense. Here are the perspectives of a few of them:

I don’t want to get into a semantic debate about whether this perspective is “racist” or not. But I think it demonstrates a kind of crude parochialism that’s morally objectionable for some of the the same reasons that racism is problematic. The kids whose lives would be transformed by the DREAM Act are, we should remember, Americans in every relevant sense. Here are the perspectives of a few of them:

My name is Blanka. I’m 23 years old and I was born in Croatia and currently live in Illinois. I came here when I was ten on a tourist visa and overstayed it without my knowledge. I have a bachelor of science in finance and am applying to graduate school to study applied statistics. I love sports, running (I just ran my first marathon), volunteering, piano, and many other things. I feel the U.S. is my home and I want to give back to a country that has given so much to me.

My name is Mario and I am a sophomore studying mathematics and economics at UCLA. I moved to the U.S. from Guatemala at the age of nine to reunite with my mother after two years of not seeing her, only to once again be apart from her due to her job as a full-time nanny for another family. Even as a single mother, she has dedicated all of her time and effort to trying to make my life easier and better than how we lived in Guatemala. Since I cannot legally work in order to support us financially, I’ve contributed to our struggle by empowering myself with an education in order to support both of us when she no longer can work. I was valedictorian in my high school and the first one in my family to go to a university, but as an undocumented student, these accomplishments are somewhat meaningless to me as I know I have to fight harder in order to accomplish my long-term goals.

Robberson is “not sure” it’s “smart” to extend basic freedoms to these kids because doing so might inconvenience native-born Americans. I suspect his empirical claim is wrong—that the DREAM Act would not significantly reduce the opportunities available to American college kids. But I also don’t really care. I think it’s wrong to condemn a 23-year-old to a life of poverty and uncertainty in the country he calls home. And I don’t think it matters whether recognizing these kids’ right to earn an honest living will depress the wages of native-born Americans, any more than it mattered whether ending discrimination against blacks made it harder for whites to find jobs.

Robberson is “not sure” it’s “smart” to extend basic freedoms to these kids because doing so might inconvenience native-born Americans. I suspect his empirical claim is wrong—that the DREAM Act would not significantly reduce the opportunities available to American college kids. But I also don’t really care. I think it’s wrong to condemn a 23-year-old to a life of poverty and uncertainty in the country he calls home. And I don’t think it matters whether recognizing these kids’ right to earn an honest living will depress the wages of native-born Americans, any more than it mattered whether ending discrimination against blacks made it harder for whites to find jobs.

After reading all the comments, both here and in response to Will Wilkinson’s post, I’m still waiting for a convincing explanation of why it’s more acceptable to deny people basic rights on the basis of national origin than on the basis of gender, race, or sexual orientation. The most common response seems to be that we’re justified in violating the human rights of illegal immigrants because a majority of Americans have voted to do so. But few Americans would accept that as a rationale for discriminating against other disfavored groups. I agree with Thomas Jefferson that all men are created equal and endowed with inalienable rights. If that’s “fanatic, indiscriminate, or dogmatic,” (to quote a friend who commented on my last post) then I think I’m in good company.

Very well said Tim. No “convincing explanation” here.

It’s completely valid to discuss problems arising from our immigration policy choices. But that shouldn’t lead to an unquestioned resentment of people who simply want happy and comfortable lives.

Hear hear. A great post; I’m feeling guilty for not seeing it sooner.

I wouldn’t be opposed to legislation like the Dream-Act if pro-immigrant activist would concede to the deportation of others unlawfully in the United States. Others like gang bangers, rapist, child molesters, drug dealers, drunk drivers, murderers, etc. It seems to me that these activists are pushing an all or nothing agenda. Sadly, this is at the expense of bright and promising students.