I’m delighted that Jerry Brito has written a thoughtful response to my recent posts about spectrum and property rights. I want to start by reiterating what I have said before: Jerry’s paper on the subject of spectrum commons is a must-read and ably lays out what might be called the standard libertarian view on spectrum policy.

Reading Jerry’s post, I got the sense that we were largely talking past each other. Jerry’s an awfully smart guy, so I’m going to take this as evidence that I didn’t make my argument very well in my last post. So let me see if I can make my argument in a different, and hopefully clearer, way.

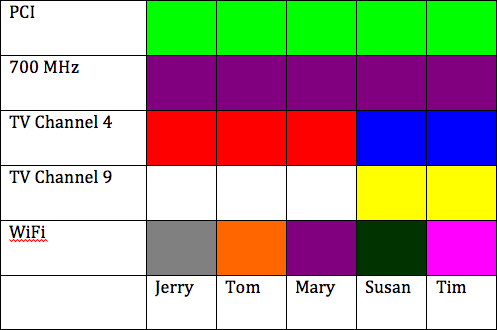

Here’s a simplistic and stylized schematic of the current spectrum regime:

Status Quo

The columns represent real property owners, and the rows represent spectrum blocks. Jerry, Tom, and Mary are representative property owners in the Washington DC area, while Susan and Tim own property in the Philadelphia metro area. Each color represents a distinct spectrum licensee. So in this case, we see a 700 MHz spectrum block and a PCI spectrum block, each of which is held by a single owner across all the properties in the chart (these would probably be big companies like AT&T or Verizon). Then we have two different TV channels, which are held by different parties in different metropolitan areas. One of the channels isn’t being used at all in the DC metro area (which is one reason we need spectrum reform!). Finally, we have the WiFi band. I’ve colored these separately to illustrate the fact that, in effect, each of these property owners has a license to transmit within the boundaries of his or her own property.

Now here are two possible changes to the spectrum regime. The first is what I take to be Jerry and Tom’s ideal spectrum policy regime. In this picture, we’ve auctioned all frequencies so that each has been licensed to a distinct private party, with regulations to prevent spectrum users from interfering with users on adjacent frequencies:

And here’s another allocation that we might call the “WiFization” of the electromagnetic spectrum. Here the entire electromagnetic spectrum is allocated for unlicensed use on the WiFi model, with regulations to prevent spectrum users from interfering with geographically adjacent users:

If I’m reading Jerry right, he thinks one of these depicts a free-market system based on property rights, while the other is “command and control” regulation. This strikes me as kind of silly. From a philosophical perspective, these two situations are almost perfectly symmetrical. The only difference is how we’re drawing the property boundaries.

In particular, the difference is not that in one picture the government sets the rules and in the other picture private parties set the rules. In both cases, the government delegates authority to private parties along with some general rules designed to prevent parties from interfering with one another. It’s not obvious that one regime requires significantly more onerous or complex rules than the other.

Indeed, you could imagine implementing the “WiFi” regime using a common-law based non-interference rule rather than a specific power level mandated by the FCC. We could even do away with the FCC altogether! Neighbors would negotiate among themselves about power levels (and cut deals for permission to transmit across each others’ property), with the courts hearing disputes and gradually developing a body of caselaw about reasonable power levels. I don’t know how practical such a regime would be, but it’s certainly not a “command and control” regime.

But let’s get back to the real world, where we do have an FCC and it’s not about bring about either of the sweeping reforms I depict above. I think the heart of Jerry’s argument is this:

I think we have to ask ourselves, why do we (both on the left and the right) dislike command-and-control? The main reason, it seems to me, is what Hayek called the local knowledge problem. A central authority like the FCC can’t possibly have all the information it needs to allocate scarce resources efficiently…

If the resource is controlled by the state, and it is setting the rules, then the only means available to it for setting the rules is a command-and-control process subject to the knowledge problem noted above. On the other hand, a property rights approach to rule setting is dynamic and bottom-up, something I know Tim will appreciate. So, I don’t think that Tom and I are conflating the first order question with the second order question. I think we are conflating a state-governed commons with command-and-control regulation, because that is in effect how the state creates commons.

This is precisely the kind of argument I was critiquing in my pizzaright post. The basic argument is that if the government controls a resource, that’s “command and control,” and it’s subject to Hayek’s knowledge problem. But if a private party controls the resource, we’ll get bottom-up solutions. To see what’s wrong with this, imagine if we implement a “property rights” regime in which we clear out the entire electromagnetic spectrum and auction it off to a single owner. You could call that a “property rights” system, but most people would just call it a monopoly. And this monopoly would be subject to precisely the same knowledge problem as the FCC. Central planning is hard regardless of whether you’re a private company or a government agency.

This problem gets less severe as you auction off more licenses. But it never goes away completely. Granting exclusive nationwide (or even regional) licenses necessarily privileges large-scale, capital-intensive, centralized business models, while hobbling small-scale, bottom-up business models. Unlicensed bands distort the market in the opposite direction.

Of course, clever market participants may discover ways to allow decentralized experimentation using centrally-controlled spectrum blocks. But the point of my pizzaright analogy was that markets never fully overcome these costs. Pizzarights will always skew the pizza market and disadvantage smaller pizzarias. And in exactly the same way, a system of exclusive national spectrum licenses will always be more friendly to top-down technologies like cellular than bottom-up ones like WiFi.

Just to reiterate: that doesn’t mean exclusive licenses are a bad idea. There are some extremely useful applications that can only be accomplished in top-down fashion, and I’d like to see more exclusive licenses auctioned off for those applications. But I would also like to see more spectrum made available for unlicensed use. And I don’t think that makes me an enthusiast for central planning.

How about letting anyone use any damn frequency they damn please? Now that’s freedom. What gives the government the right to auction spectrum? This is not a rhetorical question. Let me hear the answer from our Libertarian friends. I’ll wait.

Still waiting.

It sure would be nice if licenses would expire more often, especially to owners and operators that are not local or not providing service locally.

But that would indicate a need for a more proactive FCC, no matter the direction that licenses are in – frequency or area.

@comment #1: What gives the government the right to auction frequency is the same right to auction land, mineral, or water rights. That’s a pretty easy question.

You don’t argue about letting anyone sleep anywhere they wish, do you?

rapier,

Basically, the answer is that a frequency in the EM spectrum is much, much more valuable if a business can be guaranteed that they have sole use of it. Without that guarantee a broadcast network would be far less valuable.

A sort of compromise might be to have a band of frequencies that are free for anyone to use and others that are restricted as all are now.

Tim,

In standard economic theory, wouldn’t the best thing to do be to have the entity creating these properties make sure it sold them for the highest price it could collect?

Who has a problem with command and control? If we didn’t have government run industrial policy we wouldn’t have mass production, electricity or computers. Letting the market pick winners and losers means that all we’ll wind up with are losers.

The FCC allocated frequencies because private parties often infringed on each other’s claims. Even when they weren’t trying to blast each other, they discovered that a reasonable day time allocation would cause problems at night when signals were stronger. So, the government stepped in and allocated frequencies based on the existing technologies which made the most sense with a relatively small number of expensive transmitters operating at fixed frequencies. The technology has changed, and we could move to a lot of smaller transmitters based on adaptive use of frequency, just as we allocate lightly used traffic intersections. The issue is strictly political. Politics is how we use the government to make important decisions like this, but right now, the large transmitter, fixed band model is way too profitable to dislodge. If we had a suitably flake-ball left wing government, it might move to a more cellular model, but I don’t see it happening soon.

An economically rational government would obviously try to maximize overall tax revenues, along the lines of Faraday’s apocryphal “Some day, sir, you may tax it.” In practice, it revolves more around reelection prospects and the need to afford expensive time on large transmitters with fixed frequencies.

MSR: it’s not that simple. Look at it this way. If the US government’s goal were to maximize auction revenue, probably the way to do that would be to auction off the entire electromagnetic spectrum to a single company. But the high sale price wouldn’t represent greater value to consumers. Rather, it would mostly represent monopoly rent extraction.

This is the point of the pizzaright analogy. In a frictionless world, pizzarights wouldn’t reduce the efficiency of the pizza industry because pizzaright holders and small pizza firms would always be able to strike a deal that allows the pizza firms to exist. In the real world, administrative inefficiencies and desire to maximize rent extraction would cause pizzarights to destroy a lot of value, even if they were auctioned off to the highest bidder.

Revenue to the licensee is not identical to consumer benefit, and the wedge between the two is likely to be larger for some applications than others. It may be (in fact, I suspect it is) true that the WiFi band produces more overall consumer value, but that would be hard to organize the WiFi market in a way that allowed a single spectrum owner to capture a large fraction of that value. So a private owner may find it more profitable to set up a top-down cellular network even though the total value (to consumers) of the WiFi network it replaced is higher.

The problem you all have is that you don’t understand or believe in INVENTION. Across the spectrum, this is actually the most important part.

Example: right now the KA band (satellite) is owned and used by companies that:

1. are dying.

2. shoot a broadcast signal WAY TOO HIGH for it to be responsive as two-way.

But if you dangle standard satellite equipment off a blimp floating at 60K feet – all of the sudden the spectrum’s value changes. Suddenly a silly little blimp can light up a 300 sq mile area with viturally:

1. unlimited broadband.

2. unlimited TV

3. unlimited fone.

That’s right, a blimp can make cable companies obsolete – a blimp can make a desert a suddenly massively connected piece of land.

THE BULLSHIT about command and control is that UNLESS some slick bastards can buy up a dying thing OWN IT and change the dynamic – the new tech doesn’t happen.

You are dumb children. Stop trying to out think the world. GET OUT OF THE WAY.

Property rights MAKES dead assets EXPLOITABLE. And that’s where profit and good things come from.

God, hippies need punched.

Tim,

Thanks for the response. I will need to read and think about the pizzaright article. I only just showed up here. Also, let me say that I’m arguing not from a deep knowledge of the issues, but on the principal of “what makes sense to me” and I do know how limited that is.

On that note, I have to say that you claim about the frequency being bought up by one entity doesn’t make sense to me. I would think that any one entity could only make so much use of the whole spectrum and thus could only expect to generate so much revenue with it. Some other, smaller scale business would likely believe they could use a fraction of the spectrum to make more money than that fraction represented of the first entities revenue. In which case the second business could offer more and the licensing agency would maximize revenue by selling off the smaller piece. This would seem to be multiplied across the spectrum, maximizing revenue by selling it off in smaller pieces. I’ll think about it.

MSR, see here for an explanation of why selling to one firm would maximize auction revenues.

I would be more sympathetic to this debate if spectrum interference were not a complete fallacy. The only difference between Radio Frequency (RF) spectrum and visible light spectrum is wavelength, which only affects some of the transparency and reflective properties of solids. Light is light, with the same general physical properties, whether it’s human-visible or not. Saying that RF emitters in a given frequency “interfere” is just like saying that a red fire truck “interferes” with seeing an adjacent red fire hydrant. You only need a decent camera (focused light sensor array) to tell the two apart.

Proximity, energy, and relative viewing angle might make differentiating any 2 given light sources of the same color (frequency) more difficult, but never impossible. The only real limitation is the viewer’s sensing equipment. The only reason no one has made better RF sensing equipment is because the FCC and similar international bodies have sold off RF color monopolies. These color monopolies grant energy-abusive license to use brightness levels that saturate whole geographic regions, and make better sensing equipment cost ineffective to develop. It’s literally a case of the blind (to RF light) leading the blind.

Fred, directed transmissions aren’t practical in every situation. I can’t imagine how you’d design a cell phone, for example, whose antennas were always oriented toward a specific transmission tower. Given that you want omnidirectional transmission and reception for many applications, interference is going to be a problem. Better technology can mitigate it, as it has in the existing unlicensed bands, but it’s not going to make the problem go away entirely.

Tim, I just found this month-old blog entry. Please take a look at “Shared or exclusive radio waves? A dilemma gone astray” by the Belgian economist Benoît Pierre Freyens. It recently appeared in the journal “Telematics and Informatics” (Vol. 27), pages 293–304 (paid access to the PDF online via ScienceDirect). Benoit argues that advocates of licensed and license exempt spectrum are talking past each other, ignoring their common ground, and this is both unnecessary and counterproductive since regulators actually have many more options than just these two pure cases. This is a stronger presentation of an argument I made in “Beyond Licenced VS. Unlicenced: Spectrum Rights Continua” (2007) – http://www.itu.int/osg/spu/stn/spectrum/workshop_proceedings/Background_Papers_Final/ITU-Horvitz-FINAL.pdf.

On the question of where government’s get the right to allocate spectrum, see “Marconi’s Legacy: National Sovereignty Claims in Radio” (http://ssrn.com/abstract=1107832). In fact, national sovereignty claims are pretty flimsy, and when extended to higher and higher frequencies – to visible light, for example – they are downright absurd.