Third and Chestnut Streets, March 1, 1940, shortly before it was demolished to make room for what became the St. Louis Arch. Photograph from Landmarks' collection.

Jane Jacobs wrote Great American Cities in 1961, a time when elite opinion was almost uniformly hostile to the urban lifestyle. American policymakers at all levels of government pushed policies that undermined urban neighborhoods and pushed people into the suburbs.

St. Louis, where I lived between 2005 and 2008, is a textbook example. Consider the St. Louis Arch, which began as a Depression-era project to “revitalize” downtown St. Louis by leveling about 20 blocks of prime riverfront real estate to make room for a park. Not surprisingly, this plan drew fierce opposition from the people who were living and working in those 20 blocks. But the government used its power of eminent domain to take the properties over their objections. (As an aside: the Arch is formally the centerpiece of the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial. There’s something perversely fitting about the fact that thousands of people were forcibly evicted from their land to make room for a monument to commemorate the forcible eviction of Native Americans from their land.)

Anyway, after a few years of litigation, demolitions began in 1940. Then the project got bogged down in budget problems and more litigation, and so the area was used as a gigantic parking lot for two decades, before work on the arch finally began in 1963.

Meanwhile, work began on the urban portion of the Interstate Highway System. Planners in St. Louis, as in most American cities, decided that the new expressways would run directly through the cities’ downtowns. One of them (I-44/I-70) now runs North to South between the park and downtown. Not surprisingly, if you visit the park today you’ll find a light sprinkling of tourists, but nothing like the throngs of locals you’ll find in successful urban parks like New York’s Union Square, Philadelphia’s Rittenhouse Square, or DC’s Dupont Circle. Whatever “revitalizing” effects the park might have had on the rest of the city were undermined by the fact that the park isn’t really accessible to pedestrians in the rest of the city.

Meanwhile, work began on the urban portion of the Interstate Highway System. Planners in St. Louis, as in most American cities, decided that the new expressways would run directly through the cities’ downtowns. One of them (I-44/I-70) now runs North to South between the park and downtown. Not surprisingly, if you visit the park today you’ll find a light sprinkling of tourists, but nothing like the throngs of locals you’ll find in successful urban parks like New York’s Union Square, Philadelphia’s Rittenhouse Square, or DC’s Dupont Circle. Whatever “revitalizing” effects the park might have had on the rest of the city were undermined by the fact that the park isn’t really accessible to pedestrians in the rest of the city.

Planners pursued the same basic scheme in other American cities. And in almost every case, they encountered fierce resistance from people already living where the freeways were supposed to go. Jacobs herself was a key player in the famous, and ultimately successful, effort to stop a proposed freeway through lower Manhattan. After decades of bitter conflict, similar plans were defeated in Washington, DC. Urbanists were partially successful in Philadelphia. They killed the Crosstown expressway, which would have cut through South Philly, but they failed to stop the Vine Street Expressway, which ran north of downtown and contributed to the destruction of Philly’s Chinatown.

Cities generate wealth by bringing large numbers of people into proximity with one another. Two adjacent high-density neighborhoods will be richer than either could be alone because businesses at the edge of each neighborhood will be enriched by pedestrian traffic from the other. Driving a freeway through the middle of a healthy urban neighborhood not only destroys thousands of homes, it rips apart tightly integrated neighborhoods. Pedestrians rarely walk across freeways, so businesses near a new freeway are immediately deprived of half their customers. Similarly, residents near a new freeway lose access to half the businesses near them. The area along the freeway becomes what Jacobs calls a “border vaccuum” and goes into a kind of death spiral: because it contains little pedestrian traffic, businesses there don’t succeed. And because there are no interesting businesses there, even fewer people go there, which hurts the sales of businesses further from the freeway. The harms from such a freeway extends for blocks on either side.

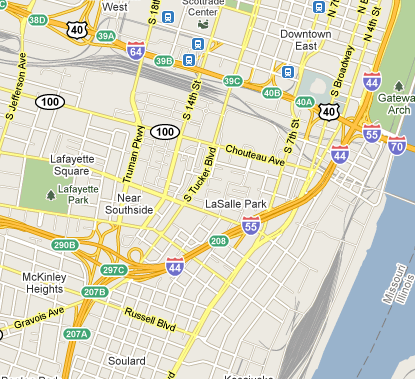

St. Louis was particularly hard hit by the freeway craze. The map at the left shows the area south of downtown, which three freeways (I-44, I-55, and I-64/40) carved up into small, atomized neighborhoods. The Soulard neighborhood, near the bottom of the map, is one of the few places in St. Louis that still fits Jacbos’s criteria for a successful urban neighborhood: it has short blocks, plenty of older buildings, and is high-density by St. Louis standards. But it’s too small to stand on its own, and the freeways have cut it off from adjacent neighborhoods to the North, West, and South.

St. Louis was particularly hard hit by the freeway craze. The map at the left shows the area south of downtown, which three freeways (I-44, I-55, and I-64/40) carved up into small, atomized neighborhoods. The Soulard neighborhood, near the bottom of the map, is one of the few places in St. Louis that still fits Jacbos’s criteria for a successful urban neighborhood: it has short blocks, plenty of older buildings, and is high-density by St. Louis standards. But it’s too small to stand on its own, and the freeways have cut it off from adjacent neighborhoods to the North, West, and South.

Going further West, similar damage can be seen in the mile-wide strip of land between I-64/40 and I-44. For example, we can compare the Central West End, where I lived for two years, with the Forest Park Southeast neighborhood further South. Between them lies Barnes Jewish, the region’s premiere hospital. The CWE is one of the most prosperous neighborhoods in St. Louis and is the preferred location for young medical professionals working at Barnes Jewish and medical students at Washington University Medical School. In contrast, when I lived there Forest Park Southest was a slum. I’m sure the reasons for the neighborhood’s decline are complex, but it certainly doesn’t help that I-64/40 runs between it and the hospital.

Carving up St. Louis with freeways didn’t just undermine individual neighborhoods, it permanently changed the region’s culture. By undermining walkable urban neighborhoods while simultaneously making it easier to commute in from the suburbs, planners effected a massive transfer of wealth from from cities to suburbs. It’s not surprising that many people responded to these incentives by moving to the suburbs. But it was hardly a voluntary choice.

63 Responses to Freeways and the Decline of St. Louis