Third and Chestnut Streets, March 1, 1940, shortly before it was demolished to make room for what became the St. Louis Arch. Photograph from Landmarks' collection.

Jane Jacobs wrote Great American Cities in 1961, a time when elite opinion was almost uniformly hostile to the urban lifestyle. American policymakers at all levels of government pushed policies that undermined urban neighborhoods and pushed people into the suburbs.

St. Louis, where I lived between 2005 and 2008, is a textbook example. Consider the St. Louis Arch, which began as a Depression-era project to “revitalize” downtown St. Louis by leveling about 20 blocks of prime riverfront real estate to make room for a park. Not surprisingly, this plan drew fierce opposition from the people who were living and working in those 20 blocks. But the government used its power of eminent domain to take the properties over their objections. (As an aside: the Arch is formally the centerpiece of the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial. There’s something perversely fitting about the fact that thousands of people were forcibly evicted from their land to make room for a monument to commemorate the forcible eviction of Native Americans from their land.)

Anyway, after a few years of litigation, demolitions began in 1940. Then the project got bogged down in budget problems and more litigation, and so the area was used as a gigantic parking lot for two decades, before work on the arch finally began in 1963.

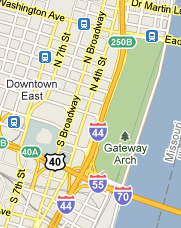

Meanwhile, work began on the urban portion of the Interstate Highway System. Planners in St. Louis, as in most American cities, decided that the new expressways would run directly through the cities’ downtowns. One of them (I-44/I-70) now runs North to South between the park and downtown. Not surprisingly, if you visit the park today you’ll find a light sprinkling of tourists, but nothing like the throngs of locals you’ll find in successful urban parks like New York’s Union Square, Philadelphia’s Rittenhouse Square, or DC’s Dupont Circle. Whatever “revitalizing” effects the park might have had on the rest of the city were undermined by the fact that the park isn’t really accessible to pedestrians in the rest of the city.

Meanwhile, work began on the urban portion of the Interstate Highway System. Planners in St. Louis, as in most American cities, decided that the new expressways would run directly through the cities’ downtowns. One of them (I-44/I-70) now runs North to South between the park and downtown. Not surprisingly, if you visit the park today you’ll find a light sprinkling of tourists, but nothing like the throngs of locals you’ll find in successful urban parks like New York’s Union Square, Philadelphia’s Rittenhouse Square, or DC’s Dupont Circle. Whatever “revitalizing” effects the park might have had on the rest of the city were undermined by the fact that the park isn’t really accessible to pedestrians in the rest of the city.

Planners pursued the same basic scheme in other American cities. And in almost every case, they encountered fierce resistance from people already living where the freeways were supposed to go. Jacobs herself was a key player in the famous, and ultimately successful, effort to stop a proposed freeway through lower Manhattan. After decades of bitter conflict, similar plans were defeated in Washington, DC. Urbanists were partially successful in Philadelphia. They killed the Crosstown expressway, which would have cut through South Philly, but they failed to stop the Vine Street Expressway, which ran north of downtown and contributed to the destruction of Philly’s Chinatown.

Cities generate wealth by bringing large numbers of people into proximity with one another. Two adjacent high-density neighborhoods will be richer than either could be alone because businesses at the edge of each neighborhood will be enriched by pedestrian traffic from the other. Driving a freeway through the middle of a healthy urban neighborhood not only destroys thousands of homes, it rips apart tightly integrated neighborhoods. Pedestrians rarely walk across freeways, so businesses near a new freeway are immediately deprived of half their customers. Similarly, residents near a new freeway lose access to half the businesses near them. The area along the freeway becomes what Jacobs calls a “border vaccuum” and goes into a kind of death spiral: because it contains little pedestrian traffic, businesses there don’t succeed. And because there are no interesting businesses there, even fewer people go there, which hurts the sales of businesses further from the freeway. The harms from such a freeway extends for blocks on either side.

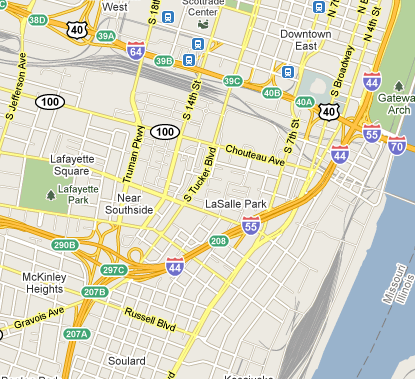

St. Louis was particularly hard hit by the freeway craze. The map at the left shows the area south of downtown, which three freeways (I-44, I-55, and I-64/40) carved up into small, atomized neighborhoods. The Soulard neighborhood, near the bottom of the map, is one of the few places in St. Louis that still fits Jacbos’s criteria for a successful urban neighborhood: it has short blocks, plenty of older buildings, and is high-density by St. Louis standards. But it’s too small to stand on its own, and the freeways have cut it off from adjacent neighborhoods to the North, West, and South.

St. Louis was particularly hard hit by the freeway craze. The map at the left shows the area south of downtown, which three freeways (I-44, I-55, and I-64/40) carved up into small, atomized neighborhoods. The Soulard neighborhood, near the bottom of the map, is one of the few places in St. Louis that still fits Jacbos’s criteria for a successful urban neighborhood: it has short blocks, plenty of older buildings, and is high-density by St. Louis standards. But it’s too small to stand on its own, and the freeways have cut it off from adjacent neighborhoods to the North, West, and South.

Going further West, similar damage can be seen in the mile-wide strip of land between I-64/40 and I-44. For example, we can compare the Central West End, where I lived for two years, with the Forest Park Southeast neighborhood further South. Between them lies Barnes Jewish, the region’s premiere hospital. The CWE is one of the most prosperous neighborhoods in St. Louis and is the preferred location for young medical professionals working at Barnes Jewish and medical students at Washington University Medical School. In contrast, when I lived there Forest Park Southest was a slum. I’m sure the reasons for the neighborhood’s decline are complex, but it certainly doesn’t help that I-64/40 runs between it and the hospital.

Carving up St. Louis with freeways didn’t just undermine individual neighborhoods, it permanently changed the region’s culture. By undermining walkable urban neighborhoods while simultaneously making it easier to commute in from the suburbs, planners effected a massive transfer of wealth from from cities to suburbs. It’s not surprising that many people responded to these incentives by moving to the suburbs. But it was hardly a voluntary choice.

Keep it up, I’m really enjoying this series of posts!

I think you’ll find cases all over the country where the presence of urban highways creates slums. It’s certainly the case in the Twin Cities. Look at I-94 between Minneapolis and St. Paul, 35-W south of Minneapolis, I-94 North of Minneapolis, and countless other thoroughfares. The areas adjacent to the highways are always worse than the areas farther away. The presence of a highway creates a swath of downgraded landscape, and the damage that results is often visible for decades.

Erik: Yep! I thought about using Twin Cities examples, but it’s been long enough since I lived there that I wasn’t sure my memory would be accurate/still true. Know of any good web-accessible articles about examples in the Twin Cities?

The unstated assumption is that this was a poor trade-off — that the damage to urban neighborhoods is too dear a price to pay for improved access to the suburbs.

Given what we know now about the environmental impact of the suburban lifestlye, maybe this is the case now, but I’m not sure the urban planners from half a century ag would have known that.

The victims of the declining neighborhoods make for more sympathetic stories than surburbanites. And it’s romantic to lament the decline of old urban neighborhoods compared to cookie-cutter suburbs.

On the other hand, these highways enabled people to make a living in the city, and have a bit of property and space in the country where their kids can run around in the lawn and grocery shopping isn’t an multi-hour ordeal. These aren’t all bad things.

I agree the downside of these decisions is not entirely appreciated. But they were not without their upsides.

John, thanks for the astute comment. To be clear, my point is not that either freeways or suburbs are bad. Many people like the suburban lifestyle, and policymakers should accommodate them by building an efficient system of roads to help suburbanites get around.

But there’s no logical connection between building freeways in the suburbs and building them in urban areas. In Washington DC, freeways like 395 stop at the edge of the city and deposit commuters on ordinary city streets. In Manhattan, freeways are limited to the edges of the island. In South Philly, the freeways run along the banks of rivers.

Obviously, it’s more convenient for suburbanites if the freeways go straight into the heart of the city. But I don’t think the advantage is very large. During peak times urban freeways get congested anyway. And in any event, I think the property rights of urbanites should have trumped the convenience of suburbanites.

A classic example of a freeway destroying an otherwise vital neighborhood is St. Paul’s Rondo neighborhood being essentially decimated by the construction of Interstate 94 between downtown Minneapolis and St. Paul. I can’t find an excellent web-accessible article summarizing things, but here is a list of books on the topic. From that page:

Sorry, I guess I messed up the link. Here it is:

http://www.mnhs.org/library/tips/history_topics/112rondo.html

There’s an interesting experiment under way here in California. They removed an elevated section of I-880 and rebuilt it 10 blocks or so to the west, to reconnect a previously cut off area.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Interstate_880_%28California%29#Cypress_Viaduct_Loma_Prieta_earthquake_1989

(Someone must be doing a study on the effects, but I don’t know of one.)

Is there any way to make freeways not divide up neighborhoods? Either by making them underground or suspended? I assume this increases the cost by a massive amount. Or perhaps, comprehensive pedestrian crossways?

I don’t really care either way, I just want it to be easy to get around and nice to live.

It isn’t my impression that the interstate highway system was initially motivated by the convenience of suburban living, if it is even today. The point was to enable cross-country driving without hitting the Palookaville town stoplight every five miles. Far less damage would have been done to urban St. Louis, and through traffic would have been better served, had I-44 run into I-64 near the current location of the I-255 bridge, or even much further south, since both of those interstates actually end in the St. Louis metro area. These interstates don’t have to hit I-70 like they do; I-55 could have made that connection. The I-70 bridge(s) over the Mississippi are parking lots on a regular basis. I suspect that there was a sentimental inclination to run I-44 along the old Route 66 (after all, everybody liked the song). Why I-64 extends west of the Mississippi river is really hard to figure, although of course in doing so it has fostered a morass of unplanned dysfunctional (in some cases unincorporated!) suburbs/housing complexes south of St. Charles, in addition to the havoc it wrought downtown. Those suburbs could just have easily been located somewhere else had the roads been run more intelligently.

> Is there any way to make freeways not divide up neighborhoods? Either by making them underground or suspended?

I think the only decent solution is to keep freeways but not ruin the urban environment is to put freeways underground. Anything above ground just takes up too much physical space (i.e. no short blocks, which Tim has already highlighted as important) and visually scars the landscape. There are still challenges when putting a freeway underground, namely figuring out how to design the entrance and exit ramps to not be huge extensions of the freeway and defeat the whole purpose of burying the freeway. For example, the one spot in Minneapolis where the freeway is underground (the Loring Tunnel) the area above it is ruined by a couple of huge overpasses (feeding Hennepin and Lyndale Avenues) that are extensions of exit ramps from the freeway.

Underground freeways are super expensive (see The Big Dig), but in an ideal world congestion pricing and/or freeway usage fees would provide funding for expensive underground freeways in urban environments.

Hi, got here from a Grist magazine tweet, great post! I just drove thru that tangled stretch of freeway this summer; loved the view of the arch as we whizzed by but totally agree with the more important point: freeways are awful to walk under.

Nobody so far has mentioned the Big Dig in Boston. When I lived there in the late nineties, you had to walk under a horrible, noisy clogged exit stretch of elevated freeway to stay on the Freedom Trail or visit the North End or see the bay, which is only a few feet away! Today, with the (admittedly, expensive) freeway buried, that zone is a gorgeous urban open/green space, pleasant to walk across, uniting 2 divided former places.

I don’t know how practical it is to eliminate more of these ugly 1950s-designed elevated highways, but every one I can think of has left the place much better! (The other is SF’s Embarcadero, which was flattened in the 1989 quake and not rebuilt. It is an awesome walking / streetcar-riding place where you can eat out on the waterfront at the Piers (closer to the Ferry Building than the really touristy stuff at 39).

Meanwhile, here in Columbus, we’ve got a short-term solution that’s not as expensive as the Big Dig and replicable anywhere:

http://citycomfortsblog.typepad.com/cities/2003/08/i670_cap.html

John:

That’s pretty cool! I’m from Cleveland, so you’re just right next door. Despite being nearby, I haven’t driven around Columbus too much (mainly just the neighborhoods around it) so I haven’t seen this. The link you posted was from 2003, how has it worked out since then?

Chris:

“Underground freeways are super expensive (see The Big Dig), but in an ideal world congestion pricing and/or freeway usage fees would provide funding for expensive underground freeways in urban environments.”

Yeah, that’s what I was thinking. If that type of transit were so valuable, seems like people would be willing to pay for it. It also seems like it would only need to be underground (or whatever non-urban-damage solution) for the relatively short time that it intersected the city. Like Tim said above, they’re perfectly fine being normal freeways right up until they hit the city, or even on the outskirts.

There are a few suspended highways in downtown Cleveland, but I can’t tell if they’re damaging the communities beneath them since it’s Cleveland, and there are lots of other damaging things going on. I think they look cool though!

I love that freeway cap in Columbus that is discussed in John’s link. Minneapolis sort of has a similar thing with the new Target Plaza, which covers part of I-394 and connects downtown to the new Twins baseball stadium (Target Field). I’d LOVE to see such a Columbus-style cap in Minneapolis to cover the awful I-94/I-35W trench just south of downtown. The trench separates downtown from the rest of the city, with the blocks just north and south of the trench being sort of dead and quiet despite the fact that they are within walking distance of downtown.

Interesting to me that several other readers immediately thought of the Twin Cities. To my mind, the Twin Cities would be nearly the perfect place to live . . . but for the fact that the integrity of both was so severely damaged by the freeways. Some of the loveliest and most accessible areas – chopped off from the rest of the city and permanently disfigured. Trolleys and trains dismantled and neighborhoods basically destroyed. It makes me crazy.

As a current St. Louisian, I appreciate your commentary and the sentiment of the damage these freeways have done. As one positive, there is a group of civic minded citizens working on pushing the National Park Service & others to remove the I-70 Freeway that separates downtown from the Arch. More information is at http://www.citytoriver.org

I’m a planner in the Chicago area, and I agree with much of the discussion here on the role of freeways in the destruction of walkable urban neighborhoods. But let me offer a few clarifications.

Suburban development was going to (and did) happen with or without freeways. People have been moving to the edges of cities to stake a new claim ever since there’s been cities. But what freeways did was alter the development pattern. Prior to interstate highways, cities grew larger, but nearly always adjacent to existing areas. After freeways, it became easier for developers to “leapfrog” to cheap farmland at the next freeway interchange and build homes there. That’s what pushed development further out at a faster pace, and created the sense that land was limitless.

As far as freeways that don’t divide neighborhoods, I’d say that doesn’t exist, at least not without extreme costs. I’d rather see high-volume boulevards or parkways that can carry lots of traffic (albeit at maybe 45 mph instead of 55 mph), with separated limited and local access, and with design and landscaping that connects the roadway with the fabric of the surrounding neighborhoods.

Lastly, it wasn’t simply and only “planners” who allowed freeways to lead to urban neighborhood distruction. In fact, it wasn’t even mostly planners. The main culprits: local politicians who wanted to have interstate highways cut through their cities so they could control patronage construction jobs. Traffic engineers whose only concern was to design roads to move cars as swiftly as possible from one side of town to the other, without regard to neighborhood impact. A real estate industry that was looking to extract value from decimated urban neighborhoods as well as farmland sites. “Planners” helped make it happen, no doubt, but they were only facilitating the wishes of the power structure.

Jess wrote:

I suspect that there was a sentimental inclination to run I-44 along the old Route 66 (after all, everybody liked the song).

The route of I-44 was set to run directly alongside the Frisco RR line so that it would replace commuter rail that had given birth to suburban communities like Webster Groves and Kirkwood. Say what you will about the Daniel Boone Expressway/Hwy 40/I-64 and its contribution to the destruction of the frankly decrepit Mill Creek Valley neighborhood, I-44 was (and is) far worse because it severed intact and thriving neighborhoods in the City of St. Louis after the rail line turns north and the interstate keeps heading east towards the river. The lesson of I-44 and I-64 is that St. Louis has always had vibrant suburbs like Kirkwood, Webster, and Clayton, at one time it just had different ways of reaching them, namely commuter rail and streetcar. Once the auto became king, rail in its various forms wasn’t good enough.

Candidly, I also strongly disagree with the characterization of the tourist traffic at the Arch. Go on a summer day; it can be packed. The grounds are adjacent to a MetroLink station and a large parking garage. The problem with I-70 is actually not that the people can’t reach the Arch, it’s that they are dissuaded from going elsewhere in Downtown after they’ve visited the Arch.

In the 60’s, activists prevented planners from building I10 along the riverfront in New Orleans. The French Quarter would have been cut off from the river and probably would not exist today (yes, they probably would have preserved Bourbon Street, but that’s just a part of the quarter).

Unfortunately, they destroyed the African American business district by building an elevated eyesore down the center of Claibourne Ave.

Excellent Post. The Interstates came as our addiction to cars grew, and that bad habit continues to grow. People need to realize the high cost of commuting in a personal automobile. Bad habits are hard to break.

Of America’s 40 largest urban areas in 1950, St. Louis ranked #1 in % of population lost by 1990, by a substantial margin. Considering the # 2,3,4,5 ranked % losers (Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Detroit, Buffalo) were all economically hurt by the steel industry collapse in ways that STL wasn’t, the negative impact of interstates on STL appears even more unique.

Downtown STL is the only place in America where 4 different primary interstate highways (not loops, belts, connectors, etc) lay within 2 miles of each other. Traffic from all 4 flows on a single bridge over the Mississippi. It is this density of interstates in an urban area that makes STL’s situation uniquely bad, for both our city and our neighborhoods.

I would speculate these terrible design outcomes were accidents of STL’s large relative size and importance in 1950 when the system was designed, its centralized geography ensuring roadways in all directions to/from other urban areas, and the cost/engineering limitations of Mississippi/Missouri River bridgework that could have accommodated more peripheral highway placement.

It seems that people also forget that so many of these interstate/freeway projects built between the 1940’s and the 1960’s and that completely gutted inner-city neighborhoods were built that way on purpose. It was called “urban renewal,” aka, “get the poor/black/ethnic people out of the city, destroy their neighborhoods and disperse them to thus neutralize/kill their power. A perfect example is the eyesore of I-35 in Austin, Texas that cuts that city in half like a scalpel. It was very purposefully created to cut off the eastside (the black neighborhood) from the west side (downtown and the wealthier neighborhoods). And it succeeded like a charm. The city’s eastside suffered decades of economic loss that it is only just now starting to recover due to gentrification (itself a mixed blessing).

A great book about “urban renewal” and the deliberate smashing of non-white communities through freeway building is ROOT SHOCK by Mindy Thompson Fullilove, M.D. The building of sports arenas was also a huge contributor to that as well, especially the huge sports complex in downtown Pittsburgh that displaced an entire, and thriving, African-American community that had one of the highest rates of African-American owned businesses of any neighborhood in the country. All gone for a sports arena and gigantic parking lot. And by design.

Probably one of the more insidious, and successful, ways white conservatives have managed to screw this country for decades.

Grew up in St. Looey, and agree with the observations here. In my adopted San Francisco, the Loma Prieta quake gave us the unexpected gift of the destruction of the downtown freeway that blocked the view of the bay from the waterfront, (what the hell did they call those awful ramps?), which is now the beautiful Embarcadero strand, aka Herb Caen Way. A fine roller-blading venue, by the way.

Besides helping to destroy the Bronx with the Cross-Bronx Expressway, Robert Moses also wanted to build two expressways across Manhattan (both of which were blocked, thank heavens). Lesser known is his plan for a massive bridge with access roads that would have run through Battery Park. That also was blocked, with the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel built instead.

Tradeoffs – like everything this is all about tradeoffs.

I for one think the overall economic benefit to a society of the free and easy movement of individuals and commerce trumps the localized benefits of having a bunch of cute, quirky, and “walkable” neighborhoods in high-density urban areas.

While it is certainly true that a bunch of professional bloggers with their fixed-gear bicycles and “go metric” tee-shirts will appreciate the ability to live in an acceptably “diverse” environment and buy couscous at local organic foods store down the block, business types like myself have far greater appreciation for the ability to make it into a city center and out again without the simple logistics of same consuming an entire day.

I come from Russia originally and go back fairly often. Very little there which is analogous to the US freeway system. When there, I am always struck by what an absolute and ungodly pain in the ass it was merely to get from place to place. Recently had to drive from Nizhny Novgorod to central Moscow. An all-day ordeal – and a big chunk of that taken up from the edge of Moscow inwards. I frequently make the same distance drive from Dallas to Houston back here in US. Can be done in 3 1/2 hours. (And note that while utterly lacking in any charm for the hipster set, both Dallas and Houston are freeway-centric economic and growth powerhouses.)

The post author seems to think it would be best to chop off all freeways at the edges of urban areas. Okay, then, that would be fine for all the Elvis Costello glasses-wearing types of the world who want to crawl all day from block to block in their Priuses or Surly Steamrollers. Less fine for everyone depending – directly or indirectly – upon the ability to get persons or products to where they need to go.

So Black 27, you think people who like cities should get screwed over so you can get around more easily? That’s a trade off, I guess, but it’s hardly a fair one.

I’ve been to St. Louis a couple times in the late 2000s. Going from the Hyatt (previously the Adam’s Mark) hotel to the park where the Arch is located. I found it to be a fairly short, seamless journey and didn’t feel too disconnected to the park. I-44 is sunk deeply enough to be minimally noticed. the only issue was crossing the feeder streets which were quite busy. However, the park itself doesn’t seem developed enough to provide amenities for city dwellers like Fairmount Park in Philadelphia and Central Park in NYC. It also seems to me that downtown St. Louis doesn’t have a whole lot of residential development compared to other cities, which makes that park a site mainly for the tourists.

Regarding Philly, it’s true that the Vine Street Expressway limited the expansion of Chinatown, but I-95 essentially cut off access to the Delaware River to a very severe degree and there has been talk about redoing that stretch of 95 to provide better access to the Delaware waterfront, but were talking Big Dig dollars to accomplish that successfully.

As mentioned here in other comments, the routing of intestates through the cities has disrupted, displaced and destroyed minority communities. Perhaps a little too late, President Clinton signed the “Environmental Justice” executive order in the early 90s, compelling Federal agencies like USDOT to evaluate the effects of transportation (and many other types) of project to minimize, mitigate or even eliminate their effect and damaging impact these projects have on these communities. There’s more awareness of this issue in the transportation community, but it won’t undo the great damage caused many years ago.

Fascinating post. It would be interesting to compare St. Louis to Milwaukee: the cities are ethnically and culturally similar and have similar population figures, but the revitalization of Milwaukee’s downtown has been far more successful than that of St. Louis’. The freeway doesn’t disrupt the city, at least nowhere near as much as St. Louis’ highways do. Another factor is that Milwaukee’s street grid is consistent and easily navigable, whereas St. Louis’ is a nightmare of streets that loop around and can run north to south and east to west. And downtown St. Louis is largely dead at night – I can’t imagine what kind of disaster it would be if the city tried anything along the riverfront like Milwaukee’s Summer Fest grounds, where a different major celebration is held on the lakefront just about every week of the summer.

I’d need to look more into it, but I’m tempted to say the building of the Arch (and if you want a really interesting timeline of the corruption and graft that went into building it, check out “Deliver the Vote” by Tracy Campbell) and subsequent crushing escalation of downtown real estate prices started what, perhaps, the freeway system finished. At the same time, I love the Arch and still can’t believe it was built – which I guess the majority that voted against it would have said, too.

Would a modern streetcar system or rollout of a far more comprehensive metro-link grid change anything?

Hey Joe,

I haven’t lived in St. Louis for 20 years, but they used to do all kinds of big things down at the riverfront. I guess the biggest thing was 4th of July. There’s also a club district fairly close by.

They still do that, but it would be a nightmare if they did something like that every weekend, as in MKE. The other problem with it, as someone mentioned above, is there’s really not much to do at the Archgrounds.

The Landing is fine, though not my favorite destination, but is a pain to get to. This is unfair, but an aphorism I’ve thought from time to time is that there are more ways to bypass downtown than there are things to do there.

To me this whole debate falls within the category of “emperor has no clothes.” Like Frank Gehry architecture, fixed-gear bicycles, and the Prius for that matter. Utterly foolish things that achieve some sort of bizarre consensus on the part of people who collectively do not wish to be uncool or politically incorrect by acknowledging the obvious.

Every time I hear someone wanting to rip up the freeways and replace them with stoplight-riddled, tree-lined boulevards I just want to scream. It is as if, in this fantasy world of theirs, the mere act of so doing will right all racist injustices, revitalize all cities, and promote an en masse migration from suburban McMansions into suitably “multicultural” high-density living on top of one another.

Uh, no. Make it more difficult to get in and out of cities and you just create even longer lines of IDLING, CARBON-BURNING traffic as all those suburbanites waste even more productive time and businesses spend even more time eyeing the far more accommodating environs of non-silly America. (And please could someone here make an attempt to explain away the success of cities such as Dallas and Houston – both of which more or less exemplify the opposite philosophy to that of what is being pushed here.)

No, I do not want to “screw over” the cities. I’m all about things like the I-670 cap and intelligent solutions for opening up what would otherwise be very valuable and productive land. But this whole idea of “tear apart our infrastructure” as any bringing any sort of macroeconomic benefit is pure idiocy. If I (or my employees) cannot get in and out of a city I’m not staying there.

I have news for the Matt Yglesias types of the world. Not everybody writes a blog for a living and walks or bikes to work in some quirky Diego Rivera-decorated little office in some former warehouse on the Upper West Side. And when I read silliness like this it appears as if it is you who wish to “screw over” the rest of us. You know, the people who actually create economic activity and thus indirectly allow you to pursue your silly little sheltered and utopian existences.

Black 27, no-one is in favor of idling, stuck in traffic, for hours. That’s why the alternative to expressways is not street driving; it’s mass transit. Which, living in Chicago, I can tell you takes less time from outskirts to downtown than even expressways do. I’m not one of those who thinks we’ll all give up our cars; just that we’ll drive them a whole lot less. And, this is not just a question of what type of transportation we prefer; it’s about finite resources.

Black27 has nailed the glibertarian patois of nihilists like Joel Kotkin and Wendell Cox. The real question is whether he’s merely parodying them or reflexively masturbating to their riffs. Great cities necessarily demand lots of movement. Freeways are one means of achieving that, although the cost is catastrophically high. You end of killing the city in order to make it mobile. Dallas and Houston have their Applebees kind of prosperity but who really wants to live there? Once the city is fragmented and sterilized to accommodate cars, there’s less reason for people to be there. Similarly, Phoenix is now a city in decline, its pathology so advanced that the growth machine that fed its metastasis has seized up. We love cities for various reasons but does anyone really love Sunbelt metroplexes? They don’t look loved and there’s a good reason for that.

I live in Lincoln, Nebraska, and I feel like this city’s relationship to neighborhoods reflects most of what’s been said here.

Lincoln’s planners decided NOT to have the freeway run through town. The I-80 is barely tangent to the far northwest corner of Lincoln — you get to and from downtown via a small spur, the 180/34.

The 180/34 cuts off a small triangular neighborhood called North Bottoms from its former relationship with downtown. As a consequence of this, and of its proximity with the University, this neighborhood has degraded into a light slummitude spiced with student-ghettoism.

Similar effects are, of course, not visible in the main body of Lincoln. However, the lack of any effective ways to traverse the city north/south or east/west — coupled with white flight to far south / far east suburbs and farther-east small towns like Eagle, means that several surface streets become very congested at rush hour, surprisingly so for a city of this size. 27th St is always congested; O St frequently; and State Hwy 2 is jammed w/b in the mornings and e/b in the evenings. So the city does not escape white flight / suburbanization effects. Nor has the city escaped a very nasty urban blight that renewal efforts have yet to make a real dent in.

Omaha, fifty miles to the north, has the 80 running E/W through it; the 480 loop around big chunks of the city center; and the 680 spur a bit off to the west. It has a lot more vitality than Omaha and a lot of very nice walkable neighborhoods (and much worse slums). It doesn’t seem to have as much of the traffic problem although Dodge Street does tend to be busy.

So while I agree that freeways can chop up a city, they’re only part of the mix. There do have to be acceptable ways to get around town, and public transit isn’t going to be an option in a lot of places, for reasons I won’t belabor here. We need to look at more of what people are, and aren’t, able to do economically in a city besides walk or drive or take public transit, in order to understand the problems American cities have.

Toronto was lucky– after she won the battle against Manhattan’s freeway, Jacobs moved here and pretty soon lead another successful battle to kill the Spadina Expressway. This saved our largest Chinatown, a ton of loft housing infrastructure, and Kensington Market.

I do a lot of driving and hate the Interstates for some of the reasons cited here. They almost always go directly through the center of large cities. Then, because of this problem, you get “loops” of additional freeways, adding to the break-ups of neighborhoods and the continung sprawl.

But the original error of putting the Interstates directly through the cities’ centers also made no sense. What it means is that if you are driving to, for example, New Orleans on I-10, you have to go through the middle of Houston and compete with the local traffic.

So I think they did it wrong originally in most places. An exception to some extent is Cleveland. The Ohio turnpike goes well south of Cleveland and if you want to go to Cleveland, you get off on a spur. This is similar to the original autobahns in Germany.

One consequence (or strategy, if you prefer) of the free way system in St. Louis was to create a tangible bifurcation of the city into black and white halves. Blacks primarily living north of I-44 and whites to the south.

Though some spillover has occurred over the years, anyone who has lived in this racially polarized city is acutely aware of the difference between North St. Louis and South St. Louis.

Re: Dallas and Houston have their Applebees kind of prosperity but who really wants to live there?

Can’t say about Houston, but Dallas is very livable, with great real estate prices (it escaped the bubble and its collapse entirely. And no, it’s not just some white-bread conformist desert; im fact it has the largest and liveliest gay neighborhoods in the entire region.

Of course we should pave over all our cities so that trolls like Black 27 can floor it while spitting out the window at all the people wearing glasses because they had the temerity to use their legs to get around.

Dallas and Houston are quite clearly the best American cities because it takes so little time to drive across them in a straight line without stopping. At 80mph, who cares what’s in the city? You could slow down to 65mph if you want to get a whiff of city life.

All that matters is having a highway exit ramp right next to the one building in downtown that you care about. And don’t forget there should be a huge parking lot with plenty of empty parking spaces. That should keep away the organic foodie types and their pathetic foot traveling ways.

I agree that most freeways cutting through downtowns have been destructive. I live in north St. Louis. However, I would caution against saying the freeways were the primary force. The decline of these cities began long before the interstate system, through a variety of factors. (But the interstate system was the last nail in the coffin.)

St. Louis faces several unique factors, because it re-charted as an independent city in the 1870’s (assumed county government roles). This action led to a land grab in the County and an incredibly complex political problem, one in which the County (separate from the city) contains over 90 different municipalities, many as small as 200-300 residents.

A good case study on the decline of St. Louis is a recent book: Mapping Decline by Colin Gordon. It examines the problems of American cities through the unique lens of St. Louis.

Regarding San Francisco and the Loma Prieta earthquake of 1989, not only did the quake help dismantle the raised freeway which cut the city off from it’s own “San Francisco” bay (as noted by a reader above); but it also damaged a spur from a freeway into the Hayes Valley area, which had been blighted by the raised freeway bisecting the area. In both cases, the state highway department wanted to replace the freeways as fast as possible. Enough local residents wanted to see them dismantled and these folks eventually won the battle against the rebuilders. The results are textbook cases of revitalizing an American city. The city has access to its bay, visually and physically. And the Hayes Valley area has blossomed with new apartments, shops, restaurants, etc. You can still look down the corridor where the elevated freeway ran – which is still more or less vacant; but the areas around have become more vibrant. I don’t think anyone realizes the psychological depression which is caused by the mass of an elevated freeway and its huge underbelly of shadows and support columns which replace cityscape. Some of the freeway has been replace by a street-level boulevard and some is still vacant. But the area is growing again. And this is only the result of dismantling an elevated freeway which ran 4 or 5 blocks!

The fact that neighborhoods and communities have been eradicated and urban life has been irreparably damaged by the growth of suburbs and spurned on by our dependance upon the automobile and the construction of freeway systems has been documented for at least the last 15 – 20 years.

Check out James Howard Kunstler’s books “Geography of Nowhere” and “Home From Nowhere” and find excellent treatises on this phenomenom.

You don’t even need to read the books or otherarticles and publications, just look at my hometown, New York City and its metroplitan area, and you get the most glorious example of how modern suburbia, the automobile, and the freeway systems have changed the look of this city.

The thought that governments and communities are still creating planned communities 40 years after the first of these social monstrosities was set up and established boggles my mind.

Why didn’t all of the criss-crossing elevated highways that inject into downtown Tokyo destroy that city? Why can the Japanese have elevated walkways, highways, and underground tunnels, that do not restrict foot traffic, by let car traffic get into the heart of the city? Tokyo has both good mass transit, good footways, and good freeways.

It doesn’t have to be either-or. Also, careful with trying to blame white-flight on highways. There are plenty of other factors governing the decline of cities and their shifting demographics.

Speaking as a suburbanite now who used to live in cities (Manhattan), with kids, I would not trade my house, privacy of my vehicle, and convenience, and space, for the crime and cramped nature of today’s cities.

I apologize to Anonymous for suggesting Dallas is without merit. That was obviously a bit of rhetorical excess on my part. I would like to make this distinction, however, between Black27’s ideal cityscapes (Dallas and Houston) and the relatively few that command our love and respect. Most American downtowns have been seriously trashed by freeways, parking lots, one-way streets, torn urban fabric, and often truly terrible buildings (government buildings from the 60s and 70s are, with few exceptions, stunningly awful).

Few American cities have been left undamaged and even smaller cities have central business districts that are forlorn and lifeless. There is no way to critically account for this damage without referencing our own vandalizing instincts as high-living American consumers. We wanted to drive, to make cars the central fact of our living arrangements, and we succeeded. The destruction of our cities happened in tandem with the pathetic suburbanization of American life and the result is a nation that is soul-sick with a lack of beauty, character, and vital cities. Even today, we hardly account for the horrible damage we did to this nation. We won’t come to terms with this horror because it’s central to the so-called American Dream. Greed, inane self-fulfillment, and boorish thoughtlessness led us to this point. It’s reflected in our politics, the coarseness of our discourse, and the often detached psyches of consumers searching randomly for meaning at shopping malls and fast-food outlets.

@Black27. You offer a false choice, and with a lot of hostility to boot. A good suburban rail system beats more freeways any day of the week in every respect. Notwithstanding Septa’s many flaws, the train lines here are vital to this region, and thank God they were constructed and left in place. Communities have sprung up around those lines and stations in an organic way that give all of us so many more vibrant choices. Sure, there are also sprawling exurban developments, and some people commute by freeway, and there are enclaves of corporate headquarters outside the city that have created some real traffic problems, but at the end of the day, our regional rail system is a wonderful thing. Any metropolitan area that lacks one is really handicapped.

Funny, I was thinking of Tokyo too when I read this. At least the parts I visited had somehow arranged to get businesses and people to not mind the elevated highways and train tracks. Probably because space is at a premium, nobody could be picky. Or maybe it’s an attitude issue. If you build a nice neighborhood under and around the highway, people will come. I also remember very high noise barriers, so that when you drove on the highway, you could only see the tops of buildings.

But let’s not necessarily imitate their road planning in all respects: streets are laid with havoc, and there are few street names. Addresses are done by reference to the nearest landmark. Bleh.

“I think the only decent solution is to keep freeways but not ruin the urban environment is to put freeways underground.” Christopher Monnier

If you don’t mind shifting the focus to the southwest, we are tremendously concerned about a project here in Los Angeles that we have been literally fighting for over sixty years. In a city entangled in a web of freeways, the Metropolitan Transit Authority and City/County officials are convinced that one more freeway connection, the 710 North Extension, will solve all the transportation problems in the County by moving more commuters and port containers by truck.

There are injunctions in place to keep the proposed surface freeway from splitting the cities north of Long Beach to Pasadena in half and to preserve over 1,000 homes and buildings. The counter proposal which has reached the environment impact stage with very little study of alternative modes of transportation, is to build a massive road tunnel. The tunnel, which is comprised of two north and south holes, will be the largest ever attempted in the world. It is estimated that the cost could reach upwards of $12 billion dollars with tolls reaching $20 one way through a Public Private Partnership. Even with congestion pricing, the cost would be too steep for most folks and they would spill off the freeway onto local streets. The toll plazas on each tunnel end and ventilation structures along the route could reach 150 feet in height and width. The houses that are not taken as a result of digging the tunnel will be sitting next to these huge structures which will be spewing concentrated particulate matter. Huntington Memorial hospital sits right next to the north end as well as the Rose Parade route. And if that isn’t enough to bother the local citizens, the risk from fire, flood, earthquake or terror attacks should. We have it all here. Imagine 300 cars in the tunnel crashing with 20 gallon tanks each. Have you heard about the Salang Tunnel?

My point in all of these facts is that it has not been shown that building more freeways reduces congestion. Tunneling under a city does not eliminate disruption to the city at all. 70% of our port containers travel to areas outside of Los Angeles. If we are to get cargo to its destination and keep automobile traffic moving, we must promote responsible transit solutions other than building new freeways. And no Black 27, we are not all Birkenstock wearing hippies out here in California. We are forward thinking people who demand 21st century solutions to modern problems. We cannot afford this expensive, impractical, senseless extension of the 710 Freeway.

Hiways and mass transit do not destroy cities.

Land speculation increases with traffic flow and

resulting higher land prices send buyers out to

the suburbs. Answer is not complex: derive all

necessary urban taxes from charges on land only

and no taxes on what people do with the land.

This results in reduced urban sprawl and

revitalization of cities.

Black27:

I live in New Orleans where the hot topic right now is whether to tear down the Claiborne Overpass erected in the late 60’s and part of the I-10 system. As remarked earlier, this was originally intended to run between the riverfront and the French Quarter. But that was successfuly beaten back and Paln B was to drive it through the most successful black business districts (at that time) in the history of the U.S., known as the Treme.

Hindsight is 20-20 and it is difficult to blame those who were involved with the decision, but time has shown it to have accelerated or even caused the neighborhoods tremendous and ahistoric decline.

Back to your comments, about Elvis Costello, Prius driving, Yglesias, blogger types who are disconnected from reality. Here’s some reality for ya: (1) The Claiborne Overpass is at the end of it “useful life” in engineer-speak; (2) the cost to retrofit it and/or make repairs to extend its “useful life” is $90 million.; (3) the cost to tear it down and replace it with a six-lane boulvard and large neutral-ground/median parkway (matching the origianal and current Uptown route) is $30 million.

Even Joel Kotkin and Wendell Cox would be proud to line up on the side of knocking it down.

New Orleans is considering tearing down parts of I-10 that run through the center of the city –

http://www.nola.com/news/index.ssf/2009/07/photos_for_iten.html