Third and Chestnut Streets, March 1, 1940, shortly before it was demolished to make room for what became the St. Louis Arch. Photograph from Landmarks' collection.

Jane Jacobs wrote Great American Cities in 1961, a time when elite opinion was almost uniformly hostile to the urban lifestyle. American policymakers at all levels of government pushed policies that undermined urban neighborhoods and pushed people into the suburbs.

St. Louis, where I lived between 2005 and 2008, is a textbook example. Consider the St. Louis Arch, which began as a Depression-era project to “revitalize” downtown St. Louis by leveling about 20 blocks of prime riverfront real estate to make room for a park. Not surprisingly, this plan drew fierce opposition from the people who were living and working in those 20 blocks. But the government used its power of eminent domain to take the properties over their objections. (As an aside: the Arch is formally the centerpiece of the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial. There’s something perversely fitting about the fact that thousands of people were forcibly evicted from their land to make room for a monument to commemorate the forcible eviction of Native Americans from their land.)

Anyway, after a few years of litigation, demolitions began in 1940. Then the project got bogged down in budget problems and more litigation, and so the area was used as a gigantic parking lot for two decades, before work on the arch finally began in 1963.

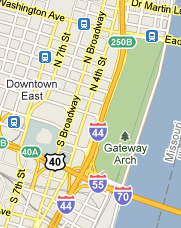

Meanwhile, work began on the urban portion of the Interstate Highway System. Planners in St. Louis, as in most American cities, decided that the new expressways would run directly through the cities’ downtowns. One of them (I-44/I-70) now runs North to South between the park and downtown. Not surprisingly, if you visit the park today you’ll find a light sprinkling of tourists, but nothing like the throngs of locals you’ll find in successful urban parks like New York’s Union Square, Philadelphia’s Rittenhouse Square, or DC’s Dupont Circle. Whatever “revitalizing” effects the park might have had on the rest of the city were undermined by the fact that the park isn’t really accessible to pedestrians in the rest of the city.

Meanwhile, work began on the urban portion of the Interstate Highway System. Planners in St. Louis, as in most American cities, decided that the new expressways would run directly through the cities’ downtowns. One of them (I-44/I-70) now runs North to South between the park and downtown. Not surprisingly, if you visit the park today you’ll find a light sprinkling of tourists, but nothing like the throngs of locals you’ll find in successful urban parks like New York’s Union Square, Philadelphia’s Rittenhouse Square, or DC’s Dupont Circle. Whatever “revitalizing” effects the park might have had on the rest of the city were undermined by the fact that the park isn’t really accessible to pedestrians in the rest of the city.

Planners pursued the same basic scheme in other American cities. And in almost every case, they encountered fierce resistance from people already living where the freeways were supposed to go. Jacobs herself was a key player in the famous, and ultimately successful, effort to stop a proposed freeway through lower Manhattan. After decades of bitter conflict, similar plans were defeated in Washington, DC. Urbanists were partially successful in Philadelphia. They killed the Crosstown expressway, which would have cut through South Philly, but they failed to stop the Vine Street Expressway, which ran north of downtown and contributed to the destruction of Philly’s Chinatown.

Cities generate wealth by bringing large numbers of people into proximity with one another. Two adjacent high-density neighborhoods will be richer than either could be alone because businesses at the edge of each neighborhood will be enriched by pedestrian traffic from the other. Driving a freeway through the middle of a healthy urban neighborhood not only destroys thousands of homes, it rips apart tightly integrated neighborhoods. Pedestrians rarely walk across freeways, so businesses near a new freeway are immediately deprived of half their customers. Similarly, residents near a new freeway lose access to half the businesses near them. The area along the freeway becomes what Jacobs calls a “border vaccuum” and goes into a kind of death spiral: because it contains little pedestrian traffic, businesses there don’t succeed. And because there are no interesting businesses there, even fewer people go there, which hurts the sales of businesses further from the freeway. The harms from such a freeway extends for blocks on either side.

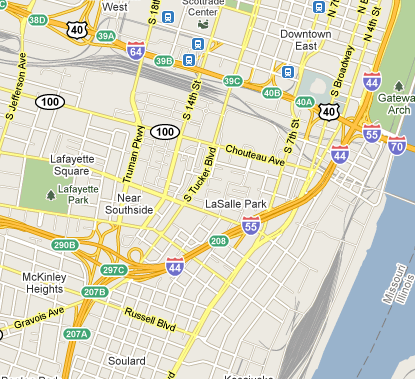

St. Louis was particularly hard hit by the freeway craze. The map at the left shows the area south of downtown, which three freeways (I-44, I-55, and I-64/40) carved up into small, atomized neighborhoods. The Soulard neighborhood, near the bottom of the map, is one of the few places in St. Louis that still fits Jacbos’s criteria for a successful urban neighborhood: it has short blocks, plenty of older buildings, and is high-density by St. Louis standards. But it’s too small to stand on its own, and the freeways have cut it off from adjacent neighborhoods to the North, West, and South.

St. Louis was particularly hard hit by the freeway craze. The map at the left shows the area south of downtown, which three freeways (I-44, I-55, and I-64/40) carved up into small, atomized neighborhoods. The Soulard neighborhood, near the bottom of the map, is one of the few places in St. Louis that still fits Jacbos’s criteria for a successful urban neighborhood: it has short blocks, plenty of older buildings, and is high-density by St. Louis standards. But it’s too small to stand on its own, and the freeways have cut it off from adjacent neighborhoods to the North, West, and South.

Going further West, similar damage can be seen in the mile-wide strip of land between I-64/40 and I-44. For example, we can compare the Central West End, where I lived for two years, with the Forest Park Southeast neighborhood further South. Between them lies Barnes Jewish, the region’s premiere hospital. The CWE is one of the most prosperous neighborhoods in St. Louis and is the preferred location for young medical professionals working at Barnes Jewish and medical students at Washington University Medical School. In contrast, when I lived there Forest Park Southest was a slum. I’m sure the reasons for the neighborhood’s decline are complex, but it certainly doesn’t help that I-64/40 runs between it and the hospital.

Carving up St. Louis with freeways didn’t just undermine individual neighborhoods, it permanently changed the region’s culture. By undermining walkable urban neighborhoods while simultaneously making it easier to commute in from the suburbs, planners effected a massive transfer of wealth from from cities to suburbs. It’s not surprising that many people responded to these incentives by moving to the suburbs. But it was hardly a voluntary choice.

There’s a good take on something similiar in How We Decide. People worry about having an extra bathroom for the 4 days a year their mother-in-law visits more than the 60 minutes they lose every day stuck in traffic. So they decide to buy a house with 3 bathrooms they can afford way out rather than one with 2 bathrooms that’s close in.

Once we recognize that, however, we can combat it. And we are.

I lived in St. Louis for 20+ years and have some issues with this post. Jacobs fanatics love to label the highways as the root of every city’s failure, yet there is so much more to the analysis that is disingenuous to analyze St. Louis or any other city this way.

1) White flight was the biggest cause of the decline of St. Louis city and likely many other cities. As a result, nearly all of the Central West End (CWE) and Soulard were completely abandoned and their houses left boarded up. Only after a major investment by developers did CWE or Soulard become the neighborhoods they are today. In fact, 15-20 years ago (depending on the exact location) you could buy a 3,000sqft rotting shell on what is now a prime street in either neighborhood from the city for $1 if you agreed to restore it.

2) One of the biggest reasons both CWE, Soulard rebirths were possible is BECAUSE OF the boundaries created by the highway/road system. Boundaries restrict supply and increase demand which is especially necessary in a city like STL that has zero population growth. If you look at homes three blocks north of the heart of the CWE (Delmar and north), you’re looking at shells for $5k and less and moderately good condition homes for $50k and less (compared to $250k-$1.5mill for the restored homes south of Delmar in the heart of the CWE). (Non-St. Louisians: Delmar road has a stigma for being the cut off point for gentrification, in fact, north of Delmar the population is 95%+ black, whereas the CWE is 90%+ white- no kidding).

If you look at other neighborhoods like Shaw, Lafayette, and Tower Grove, you notice that there are also major roadways or a highway creating boundaries in those areas. Some of the boundaries are psychological (sociological?) such as Delmar and others more obvious like 44 in Shaw/Lafayette, 64 in the CWE… Those neighborhoods too, were largely abandoned during white flight and later gentrified.

3) In St. Louis, restricted supply in these areas is necessary because there is little population of yuppies willing to live in an urban area of a small Midwestern city. For example, the Washington Ave loft district has about 12,500 people living there and has a higher density than the CWE or Soulard. I’d be willing to guess my block in NYC has more people than that. And, if you go a block north or south of Washington Ave, housing almost ceases to exist… another boundary utilized for development.

4) Finally, the biggest reason for suburban sprawl, and something Jacobs fanatics refuse to believe or at least believe they can change, is that American culture has changed. The American dream for many people now consists of a manicured lawn, a dog, a car, and a ginormous drywall box. Not surprisingly, people who have this dream end up in cities meeting those requirements.

By they way, highways, in this new culture, don’t seem to change things at all… and if you’ve ever seen a 6,000 sqft McMansion 100′ away from an eight-lane highway, then you understand.

Joey,

Thanks for the comment! You’re right that it’s a complicated issue and I didn’t mean to suggest that freeways were the only reason for the decline of St. Louis.

The key question, which you didn’t really address, is which way did the cause-and-effect run? That is, did we get urban freeways because people started to prefer an suburban lifestyle? Or did people start to prefer a suburban lifestyle because freeways destroyed urban neighborhoods while simultaneously making suburban commutes faster? I completely agree that “American culture has changed,” but that’s not necessarily an exogenous variable.

Here are a couple of follow up comments to Black27 and others.

It is true that Dallas / Ft. Worth is an economic powerhouse because of its transportation infrastructure like its airports (2 majors), rail (major distribution/commerce hub and expanding light rail) and highway system (four U.S. Interstates).

The difference and advantage of the Interstates in DFW is that they did not destroyed communities to the extent of St. Louis and Minneapolis/St. Paul, nor have they cut off access to neighborhoods like any of the cities mentioned in readers’ responses. In DFW, there are no significant projects on the table to close down freeways that travel through neighborhoods or downtowns.

There is, however, an on-again, off-again effort by Dallas city leaders and business interests to build a tollway in the middle of a river near downtown, which is bound by levies that have been declared unsafe by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The tollway would allegedly alleviate traffic on I-35W through downtown Dallas, but the tollway’s alleged intent duplicates a project called Project Pegasus that would restructure I-35W’s traffic flow through downtown. Strangely, the Dallas Morning News (city’s daily paper) and D Magazine (city’s monthly magazine) are fully in support of this tollway-in-the-river despite the risks and duplications. Perhaps a few “Tex Corleones” needed to call in favors?

Regarding the livability of the DFW Metroplex, yes, there is an Applebee’s affluence here, and overall it is gross to the max. Five thousand foot homes? Lots of ’em, and I’ll pass, thanks. The city of Dallas’ lifestyle is more tolerable, but it is physically large and its neighborhoods are disconnected because of distance, their type (suburban neighborhoods in the northern part of the city) and transportation limitations. The park system is atrocious overall because there is too much land to maintain and develop, and too few financial resources. Parts of the city are run like banana republics, with Tammany Hall-like city politicians currying financial favors as if they deserve to enrich themselves. (Google as a starting point: “Dallas”, “FBI”, “corruption” “Don Hill”).

On the bright side, there are several new light rail lines set to open, in the city and ‘burbs, including one that links DFW airport to downtown Dallas, and cycling paths are booming throughout the city. Civic leaders are pouring money the arts, and the economy is stable and weathered the recession better than most cities in the U.S. There are many jobs here.

I found Joey’s comments interestingly contrarian. The fact that naming your neighborhood and creating artificial scarcity helps with redevelopment is almost certainly true. That said, if you create your scarcity with sharp borders like highways, you eliminate the possibility of growth and expansion of the neighborhood, the possibility of your redevelopment to spur more redevelopment.

Instead of creating scarcity with borders, create scarcity with centralized infrastructure. Consider Davis Square, which gentrified over the last 30 years. In 1985 Davis got a subway station connecting it to key parts of the Boston higher education, startup, and financial industry. The resulting gentrification has spread out from the subway station radially. The neighborhood doesn’t have sharp borders, but the farther you are from the subway the harder it is to claim your property is “in” Davis. At the same time, the development of Davis has spurred development in other parts of Somerville, such as Union Square, as people are priced out and look elsewhere.

If your city has a declining population, sometimes you may need to create scarcity. But consider what happens if you succeed at attracting a steady stream of people. Will they have room to expand?

Your readers might be interested in learning more about one of the cities that ended up in the “control group” if you will of those mid-twentieth century experiments in urban planning.

Jane Jacobs moved to Toronto in 1968, where she played a key role in stopping the construction of the final portion of the proposed Spadina Expressway

(http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spadina_Expressway). Instead, of being the location of a freeway slicing the downtown Toronto core in two, the two halves of the Spadina area is the location of some Toronto’s most vibrant and beautiful urban neighborhoods: starting north and moving south toward the lakeshore, there is the University of Toronto’s stately main campus and the crowded communities surrounding it, including the Annex, a gentrified enclave of Victorian rowhouses, a huge Chinatown, revitalized in recent decades by an influx of capital from Hong Kong, the multi-ethnic Kensington Market, the Italian and Portuguese communities of College St. West, and finally, Queen Street West, defined by it’s cafes, boutiques, artists, and writers.

Completing the Spadina would have been tantamount to plunging a dagger into the heart of the city. Toronto, while far from perfect, offers a vision of what the St. Louis of an alternate quantum universe might be.

Timothy B Lee,

Thanks for the reply, I now realized I left out any thoughts on the chicken-and-egg scenario. I think highways are most likely a result, not a cause, of the suburban sprawl we see today. Looking further back into St. Louis history, the CWE was actually a country retreat for many of St. Louis’ elites. Many of the houses were built before cars and even before streets were paved with brick. Over the next hundred years, highways caught up to other developments and neighborhoods as they progressed West, Southwest, and Northwest. Of course, its a bit of a post hoc fallacy, I suppose, and I don’t have a time line to point to that proves my development first theory…

Mainly, I think its necessary to remember that unlike Manhattan, St. Louis and cities like Chicago and LA lack natural boundaries which made expansion (for any reason) much easier, especially after the invention and mass production of the automobile. Supply and demand takes over and it becomes cheaper to move away from the city, eventually the highway catches up and then its convenient too. For example, in the 90’s, areas in St. Charles were being developed despite being a 10-15 minute drive to a major highway, now that highways like 370 have been built to meet demand the drywall boxes are being built 10-15min away from 370… low land costs and the ability to build to spec presumably being major motivations.

Of course, Jacobs supporters would opt for strong intervention and zoning to avoid sprawl where there is a lack of natural boundaries, but this type of planning restricts supply, increases prices and makes moving out of cities even more financially attractive. Of course, Jacobs was a “tenants rights” advocate, whose solution to this problem was rent control… a topic for another day… suffice it to say that if you’ve tried to rent an apartment in San Fran, NYC, or Toronto, you know the effect of rent control.

Anyway, a couple more reasons for St. Louis’ sprawl:

Interestingly, the CWE was also segregated by religion early in its history, as the gated mansions on the east side of Kingshighway (Pershing, for example) were built in response to the gated mega-mansions on the west side of Kingshighway being off-limits to Jewish families. (The “original” white flight?)

Pollution played a major role, especially while coal was the dominate heat source (the pink granite Couples House on the SLU campus, was pitch black before it was restored) . There is also a theory that the north/south divide was partially a result of many downtown lakes (including Chouteau Lake, which is now the rail yard that passes under Grand just south of SLU) were so polluted that in the summer months, the southern winds made the smell in the north unbearable.

Sorry if this post is a bit all over the place, its a great topic.

Well, Joey, did you read The Death and Life of Great American Cities?

In response to your comment:

“Of course, Jacobs supporters would opt for strong intervention and zoning to avoid sprawl where there is a lack of natural boundaries, but this type of planning restricts supply, increases prices and makes moving out of cities even more financially attractive. Of course, Jacobs was a “tenants rights” advocate, whose solution to this problem was rent control… a topic for another day… suffice it to say that if you’ve tried to rent an apartment in San Fran, NYC, or Toronto, you know the effect of rent control.”

Jacobs’ solution wasn’t rent control, it was subsidized rents for those who couldn’t afford housing. She argued that the benefit was that it would promote new supply because property owners would in fact be paid market rates. The amount of subsidy could be adjusted based on a person’s income and the owner of the apartment could eventually also rent to tenants who don’t need a subsidy. New York and Toronto didn’t take her notion that the government should not be a landlord and maintained their public housing.

Freeways weren’t solely responsible for St. Louis’ decline. Poorly planned housing projects which replaced more neighbourhoods probably played a role. Freeways and neighbourhood clearance likely exacerbated racial tensions and destabilized urban communities, encouraging white flight. It became harder to get mortgages in older parts of American cities and at the same time, governments started to facilitate suburban living. All in all, I think Jane Jacobs’ writing is quite relevant in understanding why cities like St. Louis declined the way they did in the postwar period.

Sigh.

Part of the flight from the cities is that as much as we all like the services you get in a city, we can’t abide the attitude that urbanites have.

That holier-than-thou, freeways are bad, poor people are more noble than rich, and the belief that, on the one hand, just a little MORE government control will make things better, when that’s what causes the problem.

Then turning around and claiming the Arch is a monument to driving indians off their land is really just the icing on the cake.

Wrong, wrong, wrong. Dangerously and naively wrong.

Planners? Planners do not chart the course of history. Money and power charts the course of history.

St Louis changed dramatically in 1968, the year I turned 11 years old, the year that every other kid in my upper middle class private elementary school had a big nickel bag of pot stored somewhere.

What precipitated this change? Well, its hard to ignore the 1965 Voting Rights Act which gave African Americans the right to vote in America. 1965.

Shortly thereafter, possibly per the tale told in ‘American Gangster’, massive waves of debilitating drugs swept through the African American neighborhoods and the universities–and the private elementary schools. Overnight, cardigan wearing coeds adopted peasant wear and jeans. Some fee paying college student threw a firebomb at the on-campus ROTC building in May of 1970 and burned it to the ground in a 100 ft bonfire.

In 1968, huge bags of $5 pot were available in the city and in the inner suburbs–and purchased by everyone between the ages of 11 and 30. Drugs were incorporated into young lives. Overnight. Ask yourself how that happened. It wasn’t the bloody planning commission that allowed that massive influx of marijuana.

The situation in the African American communities was that much worse. As pot and hash swept through the upscale neighborhoods around WAshington University, heroin and concaine swept through the inner city and inner suburb neighborhoods of the African Americans. Newly emboldened and hopeful with the right to vote, their whole society was rocked back on its heels. The collapse was almost instantaneous. Crime surged and so did the reporting of African American crime.

In 1969, cousins and neighbors began clearing out of the beautiful inner suburbs–fleeing for the bland gypsum board boxes 45 minutes west. White flight. Fear of the crime in the African american neighborhoods.

Once the white professionals took flight, they brought their offices with them and within a decade, St Louis city was no longer a vibrant city. Restaurants lost customers, pedestrian traffic died, Clayton started a building boom.

White flight on the back of a surge in violent crime, on the back of a mysterious influx of drugs, on the back of the Voting Rights Act.

I lived through it, a block away from Washington University and that’s how it happened.

Бесплатная RPG онлайн игра Техномагия завоевала интерес тысяч пользователей различной возрастной категории оригинальным интерфейсом, геймплеем, игровым движком. Игра в стиле фэнтези совместила в себе элементы стратегии, тактики и логики. Мир Техномагии красочен и ярок, графика основана на флеш-анимации, при этом ее системные требования минимальны.

blood pressure medicine and cat [url=http://oseltamivironline.pbworks.com/w/page/36079742/History-of-Tamiflu#160] history of tamiflu [/url] okc pharmacy shooting vidieo

ritalin or amphetamines and pharmacy [url=http://oseltamivironline.pbworks.com/w/page/36079782/How-does-Tamiflu-work#577] how does tamiflu work dosages [/url] homewood pharmacy

emergency medicine residency programs in missouri [url=http://oseltamivironline.pbworks.com/w/page/36079825/How-fast-does-Tamiflu-work#067] how fast does tamiflu work [/url] national medicine

medicine internal surgery pediatrics [url=http://oseltamivironline.pbworks.com/w/page/36079869/How-long-does-it-take-for-Tamiflu-to-work#985] how long does it take for tamiflu to work [/url] berry and sweeney pharmacy ca

pfizer new sleeping medicine [url=http://oseltamivironline.pbworks.com/w/page/36079930/How-long-does-it-take-Tamiflu-to-work#232] link [/url] egypt travel medicine

24 hour kroger pharmacy [url=http://oseltamivironline.pbworks.com/w/page/36079974/How-long-does-Tamiflu-take-to-work#375] how long does tamiflu take to work [/url] alternative medicine jobs las vegas

free medicine advair [url=http://oseltamivironline.pbworks.com/w/page/36080014/How-long-is-flu-contagious-after-Tamiflu#519] how long is flu contagious after tamiflu [/url] sterling trailer sales medicine hat

patients assistance for medicines in florida [url=http://oseltamivironline.pbworks.com/w/page/36080053/How-long-is-swine-flu-contagious-after-taking-Tamiflu#940] how long is swine flu contagious after taking tamiflu [/url] diarrhea pharmacy

medicine to treat adult adhd [url=http://oseltamivironline.pbworks.com/w/page/36080083/How-long-is-the-flu-contagious-after-taking-Tamiflu#940] how long is the flu after taking tamiflu contagious longer [/url] aibm internal medicine board review

ohio pharmacy technician [url=http://oseltamivironline.pbworks.com/w/page/36080134/How-much-does-Tamiflu-cost#270] how much does tamiflu cost answer [/url] better life pharmacy complaints

evt medicine <a href=http://oseltamivironline.pbworks.com/w/page/36079742/History-of-Tamiflu#912] link sports medicine associates florida

internal medicine residency programs in nyc <a href=http://oseltamivironline.pbworks.com/w/page/36079782/How-does-Tamiflu-work#010] how early does tamiflu work albert einstein pharmacy

central and south americans folk medicines <a href=http://oseltamivironline.pbworks.com/w/page/36079825/How-fast-does-Tamiflu-work#438] link internal medicine cme jouranls

kilgore’s medical pharmacy columbia missouri <a href=http://oseltamivironline.pbworks.com/w/page/36079869/How-long-does-it-take-for-Tamiflu-to-work#691] link occupational medicine physician employment

writing a personal statement for medicine <a href=http://oseltamivironline.pbworks.com/w/page/36079930/How-long-does-it-take-Tamiflu-to-work#278] link nuclear medicine tech salary

pharmacy prereg exam revision <a href=http://oseltamivironline.pbworks.com/w/page/36079974/How-long-does-Tamiflu-take-to-work#345] how long does tamiflu take to work lincoln ne pharmacy

robots with medicine <a href=http://oseltamivironline.pbworks.com/w/page/36080014/How-long-is-flu-contagious-after-Tamiflu#161] how long is flu contagious after tamiflu appear squirel medicine

occupational medicine ur job <a href=http://oseltamivironline.pbworks.com/w/page/36080053/How-long-is-swine-flu-contagious-after-taking-Tamiflu#226] link the journal of musculosketetal medicine issn

online pharmacies imitrex <a href=http://oseltamivironline.pbworks.com/w/page/36080083/How-long-is-the-flu-contagious-after-taking-Tamiflu#070] how long is the flu contagious after taking tamiflu influenza citrical mission pharm

pennsylvania medicaid provider manual pharmacy <a href=http://oseltamivironline.pbworks.com/w/page/36080134/How-much-does-Tamiflu-cost#154] how much does tamiflu cost answer targeted marketing medicine

First, I love St. Louis. I am only a visitor, traveling full time in a motorhome slowly around the country. Recently, I was there again for a few days and the reason for the failings of the city were explained to me as the unwillingness of the city’s leaders to allow airline hubs and large corporate centers to locate there. Is this true, or part of the truth?

Also, as an aside I am curious as to the role of St. Stanislaus Kostka Church in helping the people in the failing Pruitt–Igoe project or any role they might have had in the development of the small amount of sustainable housing that is near the old hi-rise project.

Any thoughts you might share, or sources you could point me to would be greatly appreciated. Our website is pretty friendly and upbeat, but as a child of the 60s, St. Louis fascinates me. So many terrific places, such a strange downtown.

Is it the split of city and county?

BTW, a real football stadium could do wonders. I’ve heard wonderful stories about the feeling of community when Kurt Warner was your QB.