I recently had the pleasure of reading The Great Stagnation, Tyler Cowen’s excellent “Kindle Single” about the future of innovation and economic growth. Cowen makes the case that, contrary to the right-of-center conventional wisdom, the American economy is in the midst of a decades-long period of mediocre economic growth. Previous generations of Americans enjoyed an abundance of “low-hanging fruit”—cheap land, technological breakthroughs like electricity and the internal combustion engine, rising levels of education, an end to racial and gender discrimination—that allowed rapidly increasing living standards with relatively little effort. But now, he says, the orchard is getting bare. Since the 1970s, big innovations have been few and far between, and this explains the comparatively slow rate of GDP growth in recent decades.

The obvious response is to point to Silicon Valley, where there’s clearly a lot of innovation going on. Cowen anticipates this objection in his third chapter and argues that the IT revolution is overrated as a source of economic growth. Drawing on a previous book, he argues that the Internet is great for “those who are intellectually curious, those who wish to manage large networks of loose acquaintances, and those who wish to absorb lots of information at phenomenally fast rates.” But, he claims, there’s less there than meets the eye. Most people don’t spend enough time on the web for it to significantly improve their standard of living. And in any event, blogs, Facebook and Twitter don’t create jobs or produce revenue for the government, which means that we can’t count on them to drag us out of our current fiscal predicament.

By focusing on “the Internet”—and specifically Facebook and Twitter—Cowen trivializes an industry whose economic effects extend far beyond a few overhyped websites. And Cowen fails to appreciate that information technology innovations have a different economic character than the innovations that drove economic growth in the 20th century. It’s true that software innovations often make a relatively small contribution to measured GDP. But this this is less a reflection of a “great stagnation” than a sign that official economic indicators are a bad way to measure our generation’s low-hanging fruit.

To understand what makes software-powered innovation distinctive, it helps to contrast it with the industrial-age innovations that proceeded it. For most of the 20th century, innovation was embodied in physical products like cars, televisions, washing machines, and airplanes. This style of innovation is relatively easy for government statisticians to deal with. If an economist at the BLS circa 1961 wanted to know how much the television industry was contributing to GDP, he simply added up the prices of all televisions sold to consumers.

Of course, economists aren’t only interested in measuring national output at a single point of time; they want to measure how the standard of living changes from year to year. If total spending on televisions falls, statisticians need to figure out whether this is because consumers are buying fewer televisions or because televisions are getting more affordable. The distinction is crucial because the former represents a decline in national output, while the latter amounts to an improvement in the standard of living. And of course, economists have to be careful about making apples-to-apples comparisons. For example, the switch from black-and-white to color pushed up average television prices, but it would have been a big mistake to record this as a sign of televisions in general getting more expensive.

There are many important subtleties to measuring changes in economic output, and official statistics have tended to overstate inflation (and hence understate growth rates) to some extent. But the important innovations of the industrial era had some common features that made such problems manageable. They came embodied in discrete physical objects with a fixed feature set. And the value of new innovations was roughly reflected by the prices consumers were willing to pay for them. If consumers were paying twice as much for a 60-inch television as a 40-inch one, it’s reasonable to infer that the former is twice as valuable.

Now imagine an alternate universe in which industrial products did not work this way. Suppose we lived in the world of Harry Potter, and one day in the late 1950s RCA hired a wizard to wave his magic wand and transform all of the world’s black and white sets into color sets. This would clearly represent a large increase in the standard of living—a larger increase, in fact, than the non-magical process whereby people have to buy new, more expensive, televisions. Yet the government in the alternate universe would almost certainly have recorded a smaller increase in GDP. Our own BLS would see consumers buying more expensive televisions while in the Harry Potter universe consumers would be happy with the old, cheap ones. Hence, consumers circa 1970 would be wealthier in that universe than in ours, but official GDP statistics would show just the opposite.

Today these magic wands exist. For example, a couple of years ago, Google waved a magic wand that transformed millions of Android phones into sophisticated navigation devices with turn-by-turn directions. This was functionality that people had previously paid hundreds of dollars for in stand-alone devices. Now it’s just another feature that comes with every Android phone, and the cost of Android phones hasn’t gone up. I haven’t checked, but I bet that this wealth creation was not reflected in GDP statistics. And it’s actually worse than that: as people stop buying stand-alone GPS devices, Google’s innovation will actually show up in the statistics as a reduction in GDP.

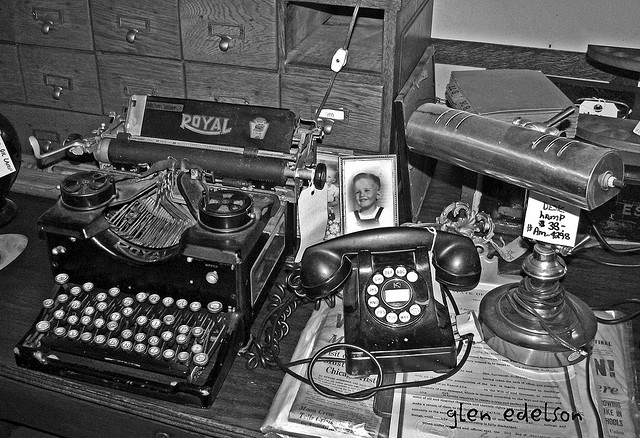

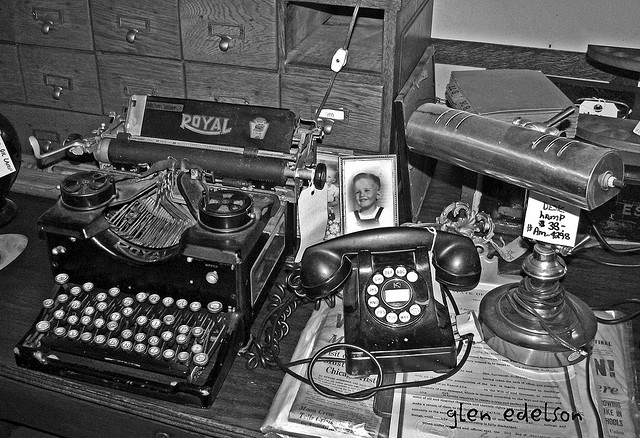

Cowen writes that the Internet is producing wealth that “is in our minds and in our laptops and not so much in the revenue-generating sector of the economy.” This isn’t exactly wrong, but it fails to appreciate the extent to which the software industry is entangled with the “revenue-generating sector of the economy.” The digital revolution isn’t just introducing novel ways to amuse ourselves, it’s rapidly displacing a wide variety of “revenue-generating” products and services: typewriters, newspapers, magazines, books, maps, cameras, film development, camcorders, yellow pages, music players, VCRs and DVD players, encyclopedias, landline telephones, television and radio broadcasts, calendars, address books, clocks and watches, calculators, travel agents, travelers checks, and so forth.

Paul Graham and Reihan Salam have been popularizing the term “ephemeralization”, originally coined by Buckminster Fuller, to describe this process whereby special-purpose products are replaced by software running on general-purpose computing devices. As the list above suggests, ephemeralization is affecting a growing fraction of the economy. And with technologies like self-driving cars on the horizon, its importance will only grow in the coming decades.

Ephemeralization offers an alternative explanation for the puzzling growth slowdown of the last decade. Every time the software industry displaces a special purpose device, our standard of living improves but measured GDP falls. If what you care about is government revenue, this point might not matter much—it’s hard to tax something if no one’s paying for it. But the real lesson here may not be that the American economy is stagnating, but rather that the government is bad at measuring improvements in our standard of living that come from the software industry.

The more subtle difference has to do with network effects and transaction costs. Dollars underpin the American economy in essentially the same way that the TCP/IP protocol underpins the Internet. The original choice of a medium of exchange was arbitrary, but people needed to pick something and once the dollar was chosen it acquired tremendous momentum. Convincing Americans to switch to a currency other than the dollar is roughly as futile as convincing the Internet to switch to a protocol other than TCP/IP, and for the same reasons.

The more subtle difference has to do with network effects and transaction costs. Dollars underpin the American economy in essentially the same way that the TCP/IP protocol underpins the Internet. The original choice of a medium of exchange was arbitrary, but people needed to pick something and once the dollar was chosen it acquired tremendous momentum. Convincing Americans to switch to a currency other than the dollar is roughly as futile as convincing the Internet to switch to a protocol other than TCP/IP, and for the same reasons.